🔮 Everyone’s looking for a bubble. No one sees the stampede.

The boring phase is coming to an end…

Five months ago, we offered the only evidence-based framework to answer the question that was taking way too much space: is AI a bubble? To get to the bottom of it through evidence rather than vibes, we tracked the five areas we believe are crucial to understand the AI investment cycle. Our indicators are: economic strain,1 industry strain,2 revenue momentum,3 valuation heat,4 and funding quality.5

Our analysis at the time – contrary to many alarmists – concluded that generative AI is a boom, not a bubble. But at the core of our approach is evidence. If evidence changes, we change our minds.

The Financial Times has published over a hundred articles invoking the “AI bubble.” Michael Burry, the famed hedge fund investor, disclosed shorts on Nvidia and Palantir, hardening his view earlier this year: “almost all AI companies will go bankrupt, and much of the AI spending will be written off.”

Fund managers surveyed by Bank of America cite AI overexposure as their top tail risk. In my discussions with people representing hundreds of billions of dollars of capital, there was some nervousness. It tended to be more nuanced than mainstream journalism portrayed – a concern of low-quality data center projects being built and funded on spec, without the guarantee of a blue-chip Big Tech tenant.

The strongest version of the bear case goes like this: capex is growing faster than revenue, model costs are falling (the DeepSeek moment proved dramatic efficiency gains are possible), and most enterprise AI is still chatbot-level stuff. In other words, enterprises aren’t getting results, efficiencies mean you’ll need less infrastructure and that capex overhang will just collapse.

But while the bubble narrative gained momentum, reality has moved the other way. And the evidence now points not just to a boom, but to something the bears haven’t considered: scarcity. The real risk isn’t that we’ve invested too much in AI. It’s that we haven’t invested nearly enough.

Today I want to close the bubble question, for now, and show why the markets should be bracing for a stampede.

The growth phase

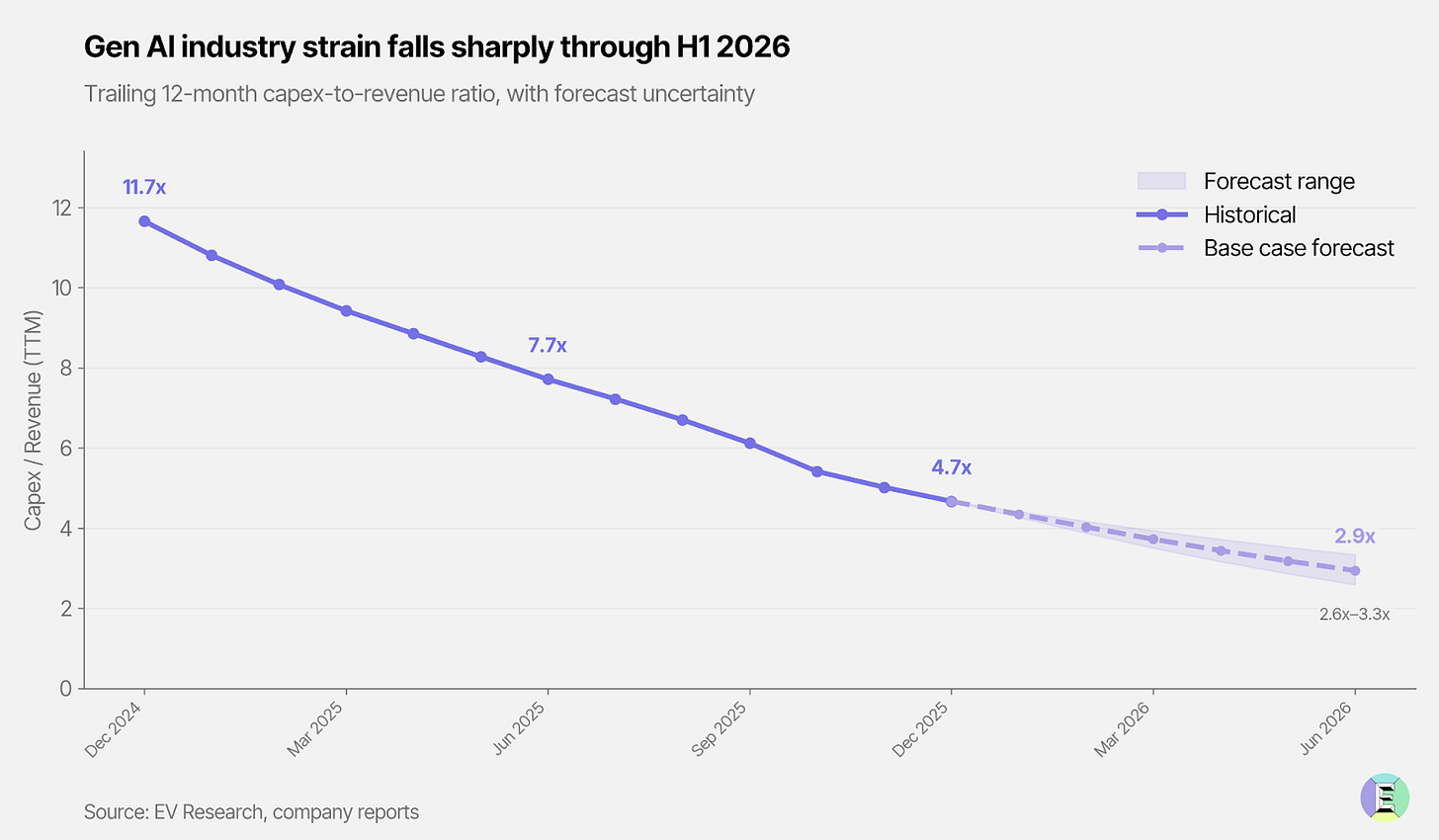

The ratio of investment to revenue – what we call Industry Strain – has dropped from 6.1x to 4.7x in five months since we published our analysis. If Industry Strain remains high for sustained periods of time, it means that companies are not recouping their investments, and they are building speculatively.

For context, the telecoms bubble peaked at an Industry Strain of just over 4x. In the case of generative AI, strain is still at historically high levels. On our dashboard, it sits in the amber zone.6 But the trajectory matters: if it holds, the ratio drops below our 3x threshold by Q2 this year. It would signal that revenues are beginning to “carry” the installed base and that the balance sheets and external financing can stop doing the heavy lifting.

Follow the revenue to understand why. According to our own proprietary model, monthly AI revenue grew from $772 million in January 2024 to $13.8 billion by December 2025, roughly an eighteen-fold increase in two years.7

The hyperscalers are the main engine. Google Cloud grew 48% year-over-year to $17.7 billion. AWS expanded 24% to $35.6 billion. Azure grew 39%, with its contracted backlog expanding 110% to $625 billion (though it’s worth remembering that 45% of this backlog is tied to OpenAI). Our revenue model estimates that AI now accounts for 23% of Google Cloud’s business, 10% of Azure’s (the biggest of which is from OpenAI) and 5% for AWS’s as of the latest quarter.

Sundar Pichai, Satya Nadella and Andy Jassy all said on their earnings calls that AI is the main driver of growth in their cloud businesses. When the CEOs of the three largest cloud companies all tell you the same story – that AI is what’s driving their growth – the attribution question starts to answer itself.

The model providers sit a tier below, and their economics tell a more complicated story. In the analysis we did with Jaime Sevilla and Anson Ho from Epoch AI, we found that OpenAI’s GPT-5 bundle achieved roughly 48% gross margins on $6.1 billion in revenue. This is decent, but well below the 70-80% typical of mature software. Worse, model lifespans are too short to recoup R&D. GPT-5’s four-month window generated some $3 billion in gross profit against ~$5 billion in development costs.8 Frontier models function as rapidly depreciating infrastructure, their value eroded by competition before costs were recovered.

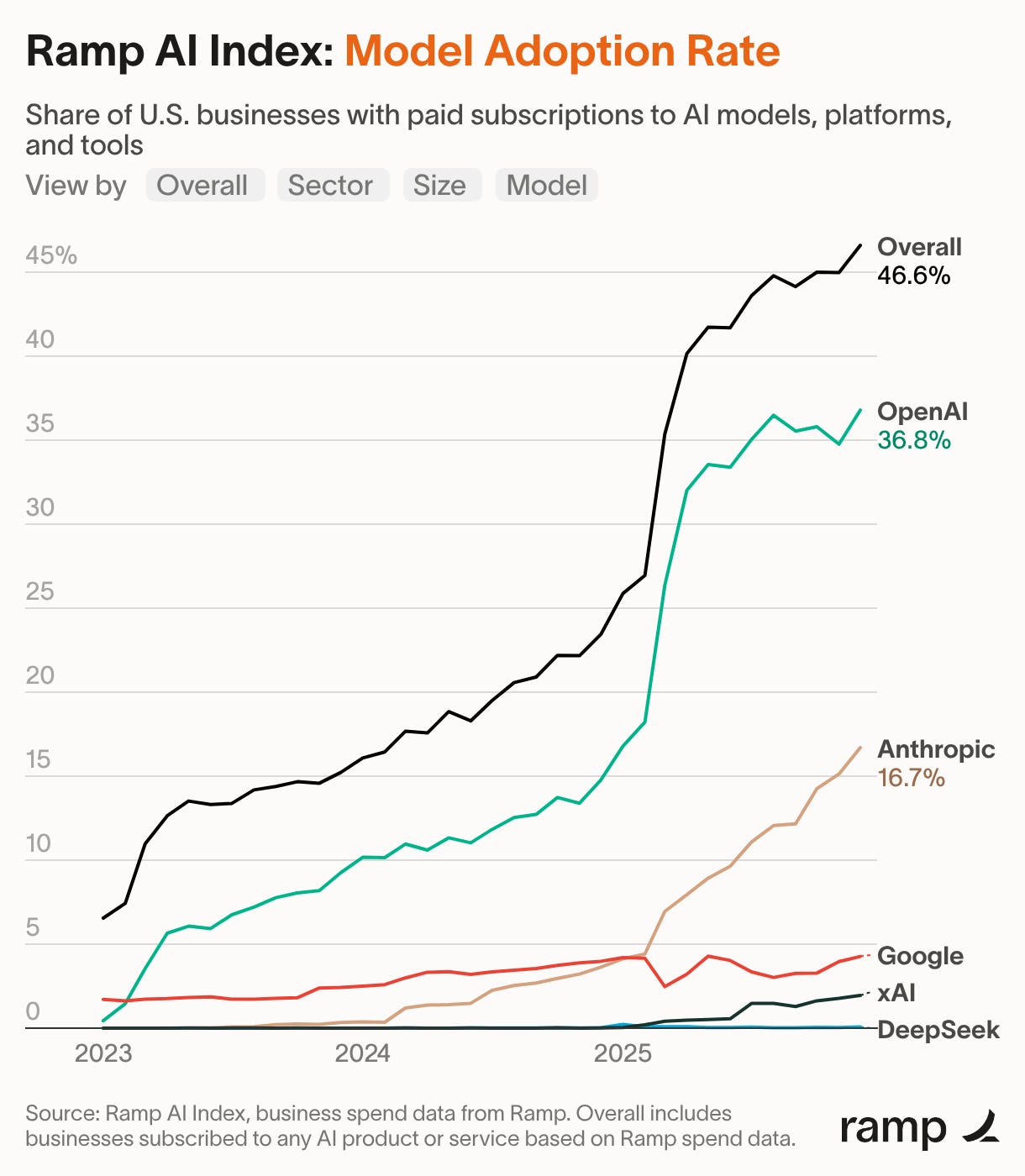

At this stage, with Anthropic chasing OpenAI on enterprise usage and OpenAI’s growth plateauing, these companies should be optimizing for growth, not profit. Positive unit economics at the gross-margin level is enough in the phase we’re in.

And growth is popping up everywhere, not just OpenAI and Anthropic. Paris-based foundation model company, Mistral, disclosed that its annualized revenue run rate exceeded $400 million, a 20-fold increase in just one year.

Boring adoption is bullish

Revenue growth is necessary but not sufficient. There’s a meaningful difference between a million users asking chatbot questions and ten thousand enterprises embedding AI into production workflows.

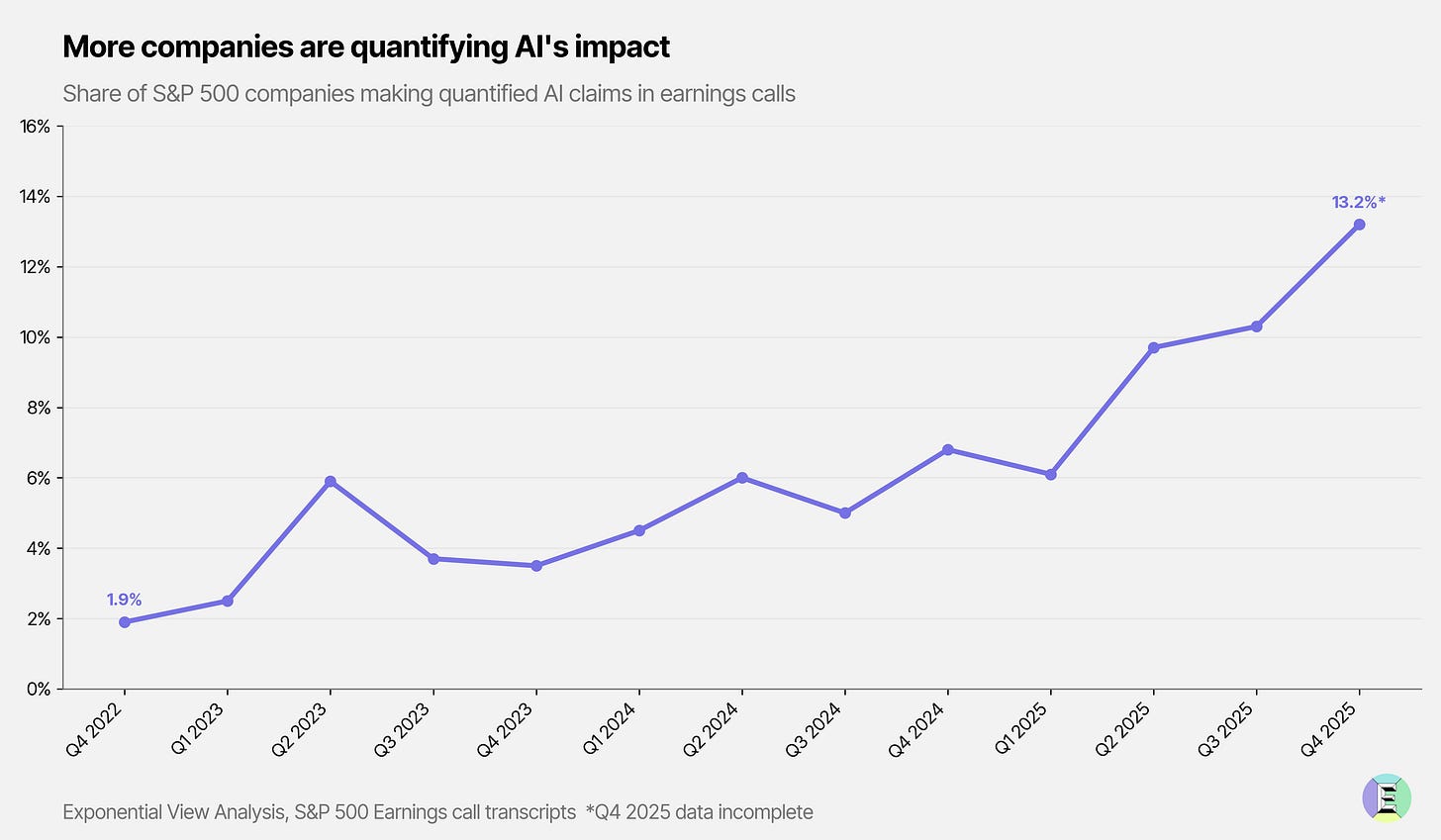

To find out which we’re seeing, we analysed more than 6,000 S&P 500 earnings calls from Q4 2022 through Q4 2025. We extracted nearly 30,000 AI-related statements. Many were corporate pabulum, but there were also specific claims about results achieved from AI projects. The share of companies making quantified AI claims (specific numbers attached to specific outcomes) jumped from 1.9% to 13.2% in that time.

When Bank of America – not a startup, not a research lab, but a 120-year-old bank –tells you AI coding tools cut their development time by 30%, saving the equivalent of 2,000 full-time engineers, the bubble debate starts to look quaint. Norway’s $2 trillion sovereign wealth fund automated portfolio monitoring with Claude, saving roughly $17-32 million per year in labor costs.9

Meta reported a 30% increase in engineering output since January 2025, most of it from agentic coding assistants. The power users have had an 80% output increase. It’s not just coding either. Western Digital, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of hard disks, reports AI tools “improving yield, detecting defect patterns through intelligent diagnostics and optimizing test processes” with productivity gains of up to 10%.

We’re looking at a technology that has crossed from experiment to infrastructure.

Most of the earnings-call claims are, honestly, boring. Percentage efficiency gains. Customer service deflection rates. Operational savings. But that’s exactly the point. Boring adoption is real adoption.

The survey data now reinforces this murky picture. Deloitte’s January 2026 State of AI in the Enterprise reports that while 25% of organisations currently have 40% or more of AI projects in production, 54% expect to reach that level within six months. Morgan Stanley’s 4Q 2025 CIO Survey shows that while IT budget growth is slowing, AI funding is increasingly coming from outside the IT department, indicating ownership by operating units rather than experimentation confined to technology teams. And in KPMG’s 2025 Global CEO Outlook, 67% of CEOs expect AI investments to deliver returns within one to three years – an acceleration from the longer three-to-five-year horizons expected just a year earlier.

There was a different timbre to the discussions with more than a dozen C-suite executives I had at Davos this year. Implementation to scale was tough, but not so tough that they weren’t already starting to think about questions about the workforce and training.

In other words, there is increasing evidence, from different sources, to show that enterprise adoption is climbing, that after a couple of years of tricky and sticky learning, bosses are doubling down. They seem to be growing in confidence over how and when they can see a return on their investment.

The agentic liftoff

And something changed right at the end of 2025, and we know what it was. Models passed a threshold of coherence; they can work very reliably on tasks of an hour or two, and somewhat less reliably on longer tasks. Something clicked. And Claude Code, Anthropic’s tool to run software agents to write software, was the first beneficiary.

We will spend some time explaining what is going on here. If you’re not at least knee deep in long-running workflows, it’s quite hard to understand the implications of these systems on revenues in the genAI ecosystem.

Claude Code is a really good software engineer. The developers building it use Claude Code to code itself. Elsewhere at Anthropic, an engineer used it to build a C++ compiler for $20,000 in API costs. A comparable project built by humans would typically require five to ten engineers over 18-24 months, around $2-3 million in fully loaded labor costs.

At Exponential View, we’ve committed (written) several hundred thousand lines of code this year alone. Many apps I use daily were written by me (with Claude Code) in the past month or so. We’ve got software running that might have cost a million bucks to write, but has only cost perhaps $500 using AI agents. These systems free up at least an hour a day for me.