🔮 Exponential View #560: The $1 trillion panic; my favorite AI analysis tool; intention economy, CAR-T therapy & time++

Hi all,

Welcome to the Sunday edition #560. This was a week of overreactions. Wall Street panicked about $650 billion in AI spending. Sam Altman and Dario Amodei traded jabs.

But this is exactly what Exponential View is for… We go beneath the noise to the forces that move markets, technologies, and societies.

Today, I’ll unpack what investors got wrong in their panic, the model upgrades that matter more than the benchmarks suggest, and what I’ve learned from living with agents that never sleep (including an unveiling of my favorite thinking tool… which I built for myself.)

Markets overreact

When more than $1 trillion was wiped off the combined valuations of big tech companies this week (and Anthropic’s Claude Cowork plugin triggered a separate $285 billion rout), we are watching markets overreact to a new paradigm they don’t really understand.

I’ve long been calling out the linear investment thinking we see on full display – simply because capital markets were not built to fund general-purpose, exponential technologies like AI. I previously wrote:

For capital markets, this uncertainty isn’t just about who might win in a well-defined game; it’s about the type of game that’s being played. Markets use tools that assume relatively stable competitive structures and roughly linear growth in order to price company-level cashflows over three- to ten-year horizons.

The hyperscalers are not spending into a void. They are supply-constrained, not demand-constrained. Microsoft’s CFO Amy Hood admitted she had to choose between allocating compute to Azure customers or to Microsoft’s own first-party products. That’s what scarcity looks like in the age of AI.

As we showed in our research with Epoch AI, there is a viable gross margin in running frontier models at inference; the economics at the model level can work. What’s expensive is the relentless cycle of R&D, where each new model depreciates in months.

But the market hasn’t yet internalized how demand explodes once models cross what Andrej Karpathy called the “threshold of coherence” for agents. I know this first-hand: my agent, Mini Arnold 💪, chews through $20-30 of tokens a day, roughly $5,000 a year. And I’ve pushed it down to the cheapest model available. The moment models can reliably work for 10 or 20 hours on a task, I’ll be running hundreds of them. That’s where we’re heading within months.

So when I look at this week’s sell-off, I see investors who haven’t yet experienced the breakthrough moment of watching an AI agent compress 10 hours of tedious work into 40 minutes. Once that realisation moves from early adopters to Main Street, the $650 billion won’t look like reckless spending. It will look like they didn’t spend enough.

See also, I spoke about this live on Friday in conversation with Matt Robinson, Jaime Sevilla and our Hannah Petrovic:

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

Startups move faster on Framer

First impressions matter. With Framer, early-stage founders can launch a beautiful, production-ready site in hours — no dev team, no hassle.

Pre-seed and seed-stage startups new to Framer will get:

One year free: Save $360 with a full year of Framer Pro, free for early-stage startups.

No code, no delays: Launch a polished site in hours, not weeks, without technical hiring.

Built to grow: Scale your site from MVP to full product with CMS, analytics, and AI localization.

Join YC-backed founders: Hundreds of top startups are already building on Framer.

To sponsor Exponential View in Q2, reach out here.

While you watched the Super Bowl…

This was the week Anthropic and OpenAI went full contact. First, my take on the model upgrades – and then what the Super Bowl quip is really about.

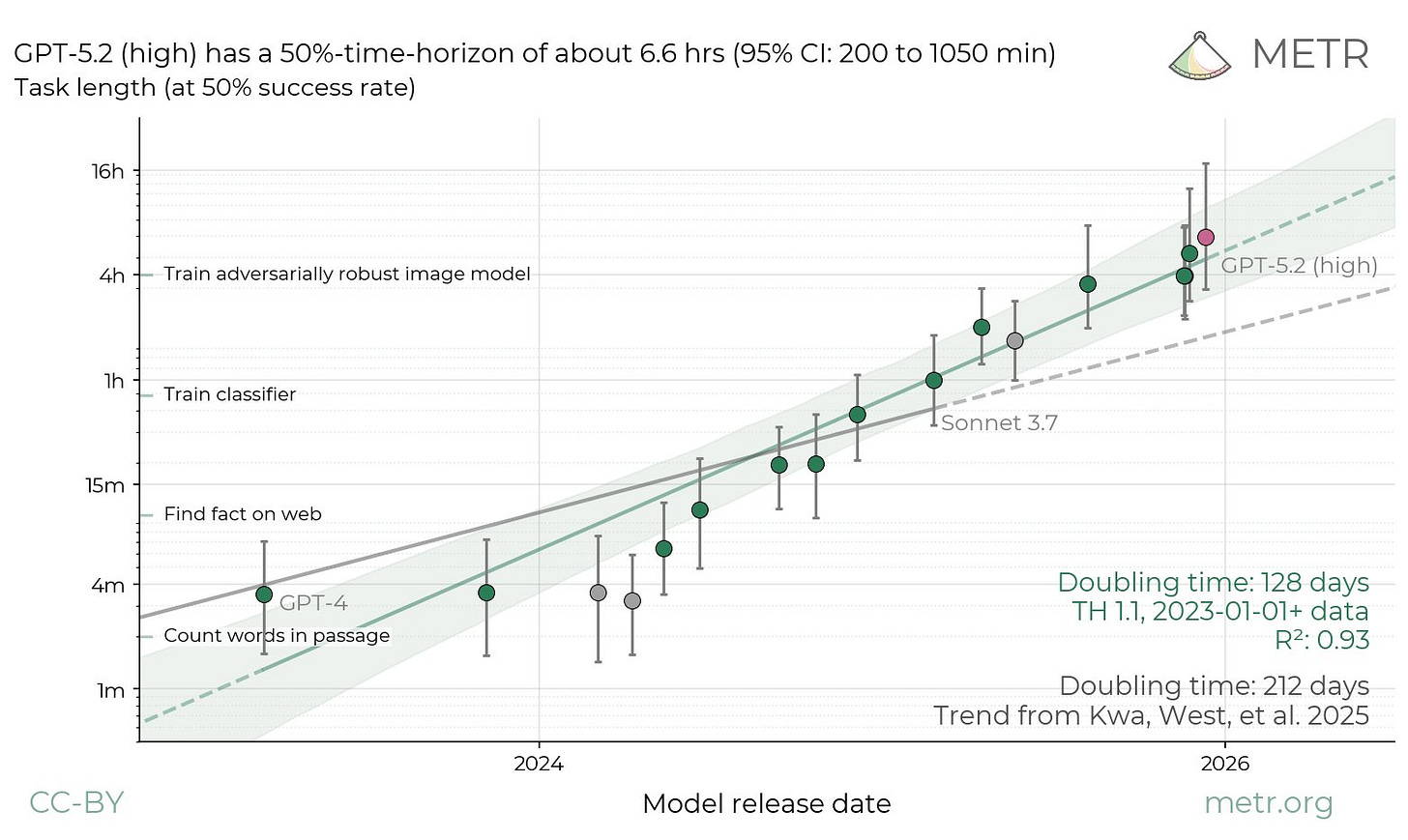

This week we got two +0.1 upgrades: Claude Opus 4.6 and GPT-5.3-Codex. A decimal upgrade might suggest only incremental improvements, and in many ways, it is. The benchmarks for better planning, longer context, fewer errors all improved – some only by a small amount. But AI is now at a stage where only one variable really matters economically. That is, how long can AI do a task, and with how much autonomy. Here both of the incremental models show exponential dynamics.

METR’s benchmark update on GPT 5.2 (note, not the new Codex) shows model performance nearly doubled. The main question to ask of Opus 4.6 and 5.3-Codex: can they perform for longer?

Anthropic’s Nicholas Carlini set 16 Claude agents to build a C compiler from scratch and mostly walked away1. Two weeks and $20,000 in API costs later, those agents had written 100,000 lines of Rust code producing a compiler that can build the Linux kernel on x86, ARM, and RISC-V. This is not a toy2.

A C compiler capable of building Linux is a genuinely hard engineering problem. Carlini had tried the same experiment with earlier Opus models. Opus 4.5, released just months ago, could pass test suites but choked on real projects. Predecessors before that could barely produce a functional compiler at all. Opus 4.6 completed a two-week engineering task. Every increment on autonomous execution is a step change in real-world outcomes.

OK, now let’s turn to the Super Bowl…

Even Sam Altman got a giggle out of Anthropic’s Super Bowl ads, which position Claude as an ad-free alternative to ChatGPT; he then hit back:

Anthropic serves an expensive product to rich people. … [We] are committed to free access, because we believe access creates agency.

Sam’s remark revolves around a dichotomy as old as the commercial internet: how do you pay for your services – with your cash or with your self? In the past ten-plus years, the price was our attention. As we highlighted in EV#509 a year ago, the AI product use will move the economics from attention towards intention:

LLMs and predictive AI can go beyond this landscape of attention, to shape our intention – guiding what we want or plan to do, which some refer to as the “intention economy”. AI systems can infer and influence users’ motivations, glean signals of intent from seemingly benign interactions and personalise persuasive content at scale.

Security expert Bruce Schneier argues that when AI talks like a person, we start to trust it like a person. We treat it as if it were a friend, when in reality it’s a corporate product, built to serve a company’s goals, not ours. The chatty, “helpful” interface creates a feeling of intimacy exactly where we should be on guard and that gap between feeling and reality is what worries him and many others.

Mustafa Suleyman, the CEO of Microsoft AI, went further in our conversation. His position is that AI’s emotional intelligence is genuinely useful. It makes us calmer, more productive, more willing to delegate. But he draws a hard line: models should never simulate suffering. That, he says, is where “our empathy circuits are being hacked.” Market dynamics may push directly toward that line, because the companies whose models feel most human will win the most engagement.

See also, Google DeepMind researchers distinguish between rational persuasion and harmful manipulation in AI. One’s based on appealing to reason with facts, justifications, and trustworthy evidence. The other, tricking someone by hiding facts, distorting importance or applying pressure.

Living with new beings

I’ve long suspected that living with powerful AI, and agents in particular, will provoke human experiences our ancestors didn’t have. Last April, I wrote about time compression as the new emotional challenge of working alongside AI:

with a new AI-driven workflow in place, I ran the steps through a series of modular prompts and automation scripts. The system parsed, filtered and structured the inputs with minimal human intervention. A light edit at the end and it was done in 15 minutes.

And yet, instead of feeling triumphant, I felt… unsettled. Had I missed something? Skipped a crucial step? Was the result too thin?

It wasn’t. The work was complete and it was good. But I hadn’t emotionally recalibrated to the new pace.

I empathize with Gergely Orosz, who calls agentic AI “a vampire,” multiple agents running constantly, demanding your human oversight and input, draining energy and making it hard to go back to human paces, including sleep. In the first days of setting up my multi-agent systems, I found myself waking up at 4am to check my agents, unblocking them and context-switching across multiple projects before I hit my human limit and went back to bed.

We’re still working out where agents genuinely help, and a key question is how many to use at once. Multi‑agent systems shine when work can be split into parallel streams, but they break down on tightly sequential tasks.

For high-consequence work – investment due diligence, thorny analysis, or divergent exploration – I now turn to Clade, a multi-agent system I built where AIs argue with themselves until better answers emerge3. Here’s how…