🔮 Why energy tech is eating the world

Farewell autocrats. Farewell cartels. Hello technology.

Hi all,

I wrote a column for the Financial Times on techno-energy reshaping the world. What follows today for readers of Exponential View is a deep dive into this question. We’ll start by exploring how energy went from being a commodity to being a technology; we’ll look at solar, wind and batteries in particular; and finally, we’ll wrap up by outlining six ways to reimagine energy. Let’s go!

Britain will unplug its last coal power station at the end of this month, 142 years since the world’s first coal power plant was built in London and 264 years since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

As the turbines fall silent, Britain will become the first G7 country to end its reliance on coal-fired electricity. Gone are the days of what English poet William Blake described in 1808 as the “dark satanic mills”.

For over three centuries, energy has been a commodity: finite, unevenly distributed and subject to the whims of markets and politics. But that paradigm has collapsed.

The “energy transition” often refers to the shift from a carbon-based energy system to a zero-emissions system. Though this change is occurring—and is crucial—the real transition we need to understand is from energy as a commodity to energy as a technology.

Unlike fossil fuels, which are extracted and burned, renewable energy is generated through innovations that improve and cheapen over time.

Energy has become a technology.

By examining the characteristics of this new energy paradigm, its key technologies and its broader implications, we can better understand and prepare for the radically different energy landscape of the future.

Energy as a commodity

Energy commodities are tradable resources like oil, natural gas, coal and uranium. And as commodities, their price is volatile and subject to “market forces.” In the case of oil, for example, those market forces have been outright manipulated starting at the dawn of the era. As early as the 1870s, John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil used tactics like consolidating competitors and secret agreements with railroads to manipulate the supply and the price of oil. A century later, OPEC’s oil embargo triggered a huge spike in the price of oil and left long-lasting ramifications in geopolitics — we still feel them today.

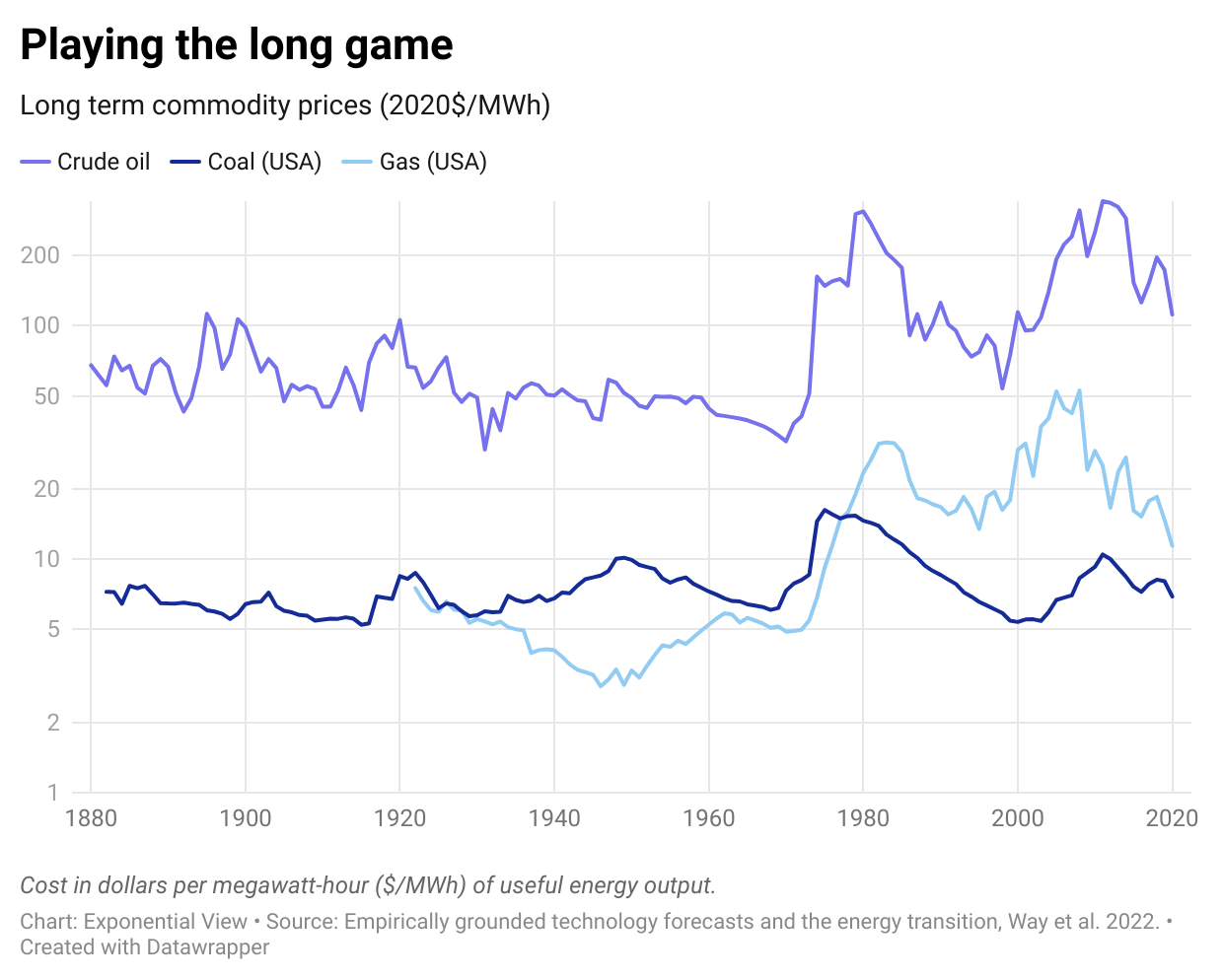

This control over supply has meant that prices haven’t decreased over time. In fact, the only thing that is certain about fossil fuel prices is that they will be volatile. Coal costs roughly the same today as it did in the 1880s. Oil is about double the price. In a century, natural gas has doubled in real terms.

And yet this inflation occurred against a backdrop of ongoing supply growth. The substantial increase in oil production as the Middle East ramped up output in the 1960s briefly brought down prices. But in 1973, geopolitical events caused oil prices to surge, much like how Russia’s political actions led to a spike in natural gas prices in recent years.

Prices remain volatile despite the discovery of new fields and technological innovations reducing the cost of prospecting, extraction and transport.

Innovation certainly occurred, but it had its limitations. Energy historian Vaclav Smil estimates that across a whole slew of diesel engines (in cars and on ships), there was an annualised improvement in engine efficiency of around 1.1% for a 16-year period before thermodynamics limited the process. But thermodynamics imposes strict limits. The Carnot cycle dictates that a heat engine’s efficiency depends on the temperature difference between the heat source and sink. For coal plants, material constraints further reduce achievable efficiencies. Modern plants reach 30-45% efficiency — below the theoretical maximum of 60-70%. Combined cycle gas turbine generators can, in the right circumstances, achieve around 60%. Physics will stop them from going any further.

So, yesterday’s energy system is at the whim of commodity prices, which depend on the mood of the local dictator. It’s no way to run a resilient future-oriented economy.

Energy as a technology

Fortunately, renewables change all that. They go beyond merely providing an alternative and competitive energy source. Much more importantly, the machines that turn wind and sunshine into electricity are technologies that behaves like the technologies of the digital world.

The underlying components, from solar photovoltaic systems, wind turbines and battery storage, are all technologies. These technologies benefit from learning curves, becoming more cost-effective as manufacturers accumulate experience.

Modularity enables and amplifies the benefits of learning curves.1 By sharing cost reductions across various market segments, it facilitates significant market expansion and nurtures an ecosystem of complementary businesses. The photovoltaic panels powering homes are fundamentally similar to those used in large-scale utility installations. This mirrors the computing industry, where the same processor might be found in both personal and enterprise-grade laptops.

But how can we be sure that renewable energy is a technology rather than a commodity?

One clear indicator is the trajectory of their prices. As technologies mature, they tend to become cheaper over time. This is especially true for technologies that are modular — composed of standardised units — and amenable to miniaturisation. Lucky for us, energy technologies have these characteristics.

What is bringing those prices down is (rapid) learning curves.

Solar and lithium-ion batteries all have learning rates above 20%. This means that for every doubling in production, prices decline by 20%.