🔮 Today’s most important technology

It’s not what you may think

GLP-1 agonists, led by brands like Ozempic and Mounjaro, have sparked a global phenomenon far beyond their original purpose. As prescriptions quadruple and waiting lists grow, these drugs are poised to reshape not just waistlines, but entire economies.

For investors, the GLP-1 revolution has triggered a stampede to understand the GLP-1 economy; and for the rest of us to understand what it all means. I’ve been tracking GLP-1 receptor agonists (or GLP-1 RAs or GLP-1s, as we’ll refer to them) since early 2022, I briefly wrote about them as temperance technologies in my January Horizon Scan and had a long discussion with Eric Topol on the topic too.

I reckon that they will be the most impactful technology in the US over the next two years, with more meaningful and measurable impacts than either artificial intelligence or renewable technologies.

In this essay, we’ll cover:

Economics of GLP-1s

Why GLP-1s work

Why I expect GLP-1s to have an outsized impact

And the three long-term future scenarios for GLP-1s.

Demand is soaring — and can be met

There is significant demand for GLP-1s. And I mean *significant*. GLP-1 prescriptions have quadrupled in the US over the last three years. Recent data shows that nearly 5% of patients receiving any prescription are now prescribed a GLP-1 RA. By some estimates, there were nine million prescriptions for GLP-1s at the end of 2023, which means that 3% of Americans are already on these drugs. The potential market is even bigger if we focus on obesity only – over 100 million adults in the US suffer from the disease (which it is, into which people often fall without blame and struggle to cure). As such, demand will keep increasing.

People clearly want GLP-1s and their makers are benefiting. Novo Nordisk, maker of Ozempic, and Eli Lilly, maker of the next-generation GLP-1 drug Mounjaro, have seen their market caps rise by over 3x and 5x respectively. Lilly became the most valuable pharmaceutical company in the world and Novo Nordisk the most valuable company in Europe, both in 2023. Novo’s sales in 2023 were so large they kept the Danish economy from contracting.

While GLP-1s were initially focused on patients with type 2 diabetes, their effectiveness for weight management has seen demand grow outside of their initial treatment purpose. In 2019, fewer than 10% of patients on semaglutide were taking it for weight control. By the middle of last year, that proportion surged to 41.7%.

As with any surge, demand has outstripped supply. Manufacturers are responding. Eli Lilly, for example, has announced a $9 billion investment in manufacturing capacity for tirzepatide, their leading GLP-1 drug. Novo Nordisk has earmarked $11 billion to expand its capacity. And every pharma company that missed out on this early wave is doubling down on their research pipeline and manufacturing capacity. So as is true in non-pharma markets, supply constraints will only be transient.

Slimming down

Besides bolstering the pockets of big pharma, the economic potential of GLP-1s comes in its second- and third-order impacts. 1 in 8 people worldwide are living with obesity. Alongside those who are overweight, they cost the global economy $2 trillion. Nearly 70 cents in the dollar is due to indirect costs – premature mortality and productivity losses associated with ill health. Without intervention, this impact is expected to double by 2035.

GLP-1s could wipe out some of this economic drag. The latest generation, Lilly’s tirzepatide, leads to weight loss of up to 22.5% of body weight. And more importantly, this isn’t a faddy diet where people rebound: the weight loss sustains itself for at least three years. Tirzepatide, marketed as Zepbound, also reduces the risk of diabetes by 94% in obese people.

Beyond weight loss, GLP-1s seem to tackle conditions right across the body. They are the preferred first injectable glucose-lowering therapy for type 2 diabetes, even beating insulin treatment. Clinical trials have found they help reduce major cardiovascular events in people with obesity, reduce sleep apnea and also lower the risk of kidney disease. These are conditions on which randomised control trials have shown GLP-1s to have an effect.

Pre-clinical trials show even more potential promise for the drug – the most unexpected is its potential effect on neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1s have been shown to restore dopamine levels and slow down the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease who received GLP-1s had 50% (!) less shrinkage in several parts of the brain related to memory, learning, language and decision-making compared to controls.

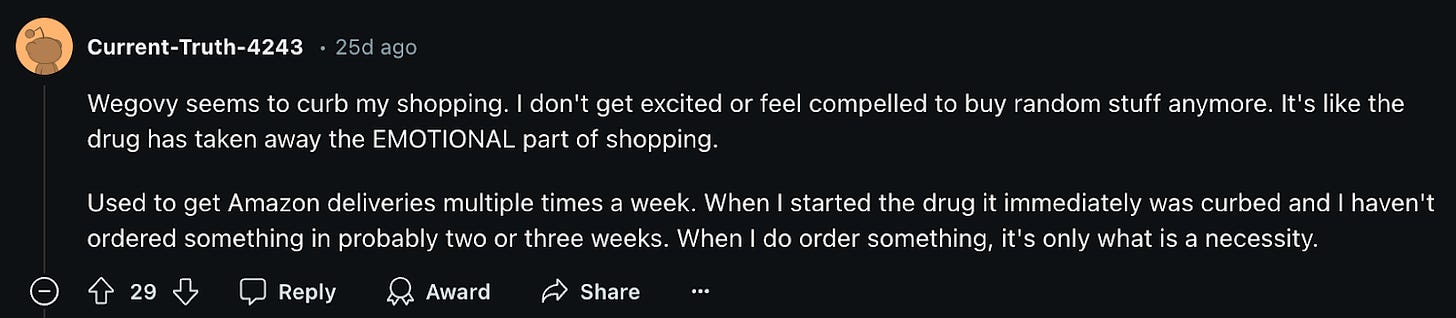

We’ve damned medicine with the phrase “wonder drug” plenty of times before. But GLP-1s might well be the real deal. Many patients using the drugs found other effects beyond those mentioned above. One realised “the desire to shop had slipped away. The desire to drink, extinguished once, did not rush in as a replacement either.”

Some Redditors are finding the same.

Caution is needed however: the study shows associative effects, not causation. And anecdata doesn’t support a revolution.

Scientists have seen that GLP-1s can reduce desire for alcohol, nicotine and cocaine in rodents and non-human primates. In a retrospective observational study published in Nature in May, researchers found human GLP-1 patients had a 50-56% lower incidence of alcohol use disorder over a 12 month period.

Like all drugs, GLP-1s have side effects, including commonly reported gastrointestinal issues and, in rare cases, more serious complications such as pancreatitis. However, our current understanding of their full long-term implications remains incomplete.

Why they work

What explains the wide-ranging potential effects of the wonder drug?1