🔮 The next 24 months in AI

A unified view of AI’s critical pressure points – and what to watch

Over the past week, I published a four-part series examining the forces shaping AI’s trajectory over the next two years. I’ve now brought those pieces together into a single, unified document – partly for convenience, but mainly because these threads belong together.

This is my map of the AI landscape as we head into 2026.

I’ve spent the past decade tracking exponential technologies, and I’ve had the privilege of spending time with the people building these systems, deploying them at scale, and grappling with their consequences — as a peer, investor and advisor.

That vantage point shapes this synthesis of where I believe the critical pressure points are, from physical constraints on compute to the widening gap between AI’s utility and public trust.

A map, of course, is not the territory. The landscape will shift – perhaps dramatically – as new data emerges, as companies report earnings, as grids strain or expand, as the productivity numbers finally come in. I offer this not as prediction but as a framework for paying attention.

Use it to orient yourself as the news unfolds. And when you spot something I’ve missed or gotten wrong, I want to hear about it.

For our members: drop your questions on this piece in the comments or in Slack, and I’ll answer a selection in Friday’s live session at 4.30pm UK time / 11.30am ET, hosted on Substack.

Here’s what I cover:

The Firm

Enterprise adoption – hard but accelerating

The revenue rocket

Physical limitations

Energy constraints limiting scaling

The inference-training trade-off

The economic engine

Capital markets struggle with exponentials

Perhaps GPUs do last six years

Compute capacity is existential for companies

The “productivity clock” rings around 2026

The macro view

Sovereign AI fragments stack

Utility-trust gap dangerously widens

1. Enterprise adoption is hard and may be accelerating

There is a clear disconnect between the accelerating spend on AI infrastructure and the relatively few enterprises reporting transformative results.

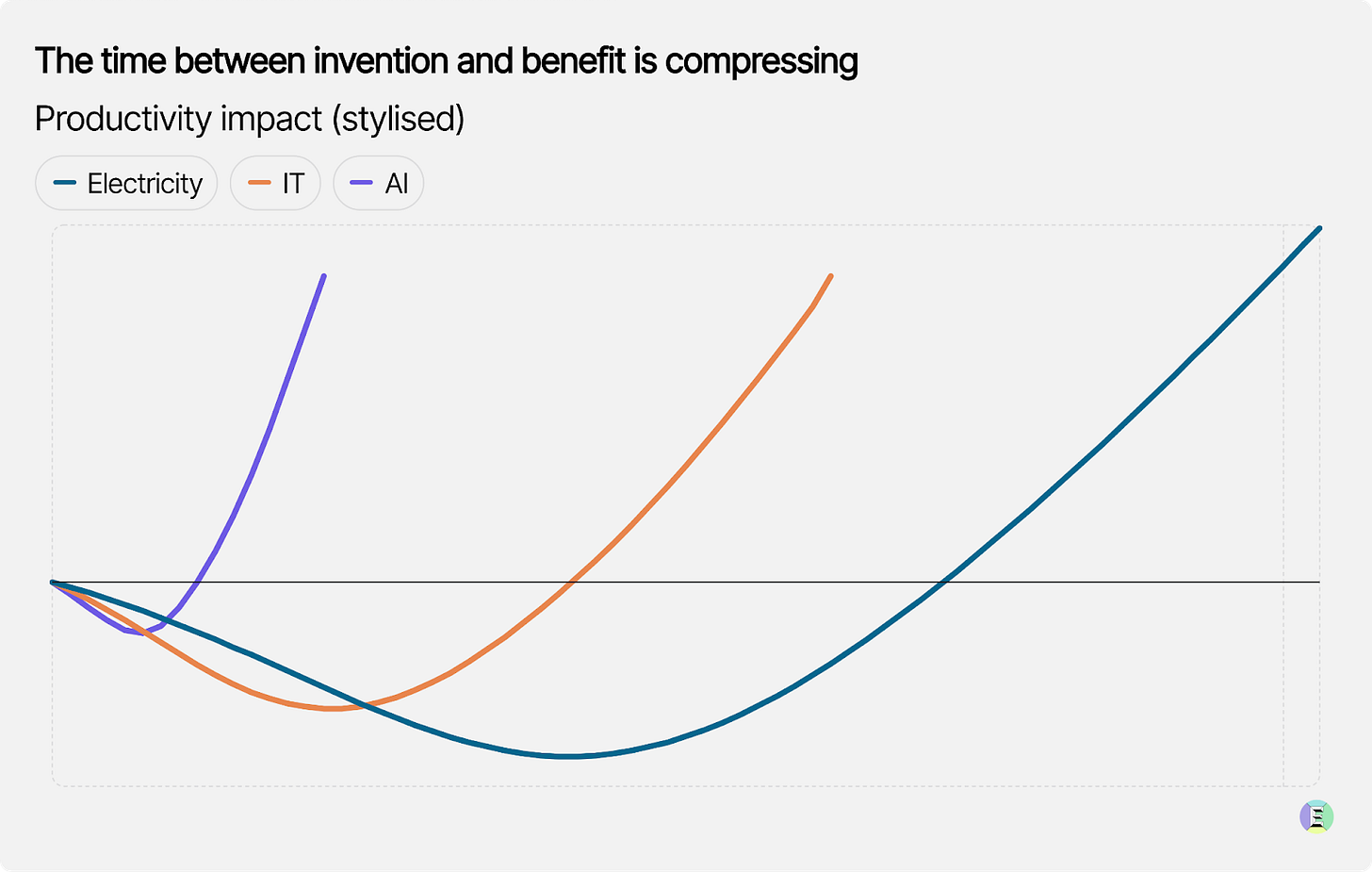

By historical standards, the impact is arriving faster than in previous technology waves, like cloud computing, SaaS or electricity. Close to 90% of surveyed organizations now say they use AI in at least one business function.

But organizational integration is hard because it requires more than just API access. AI is a general-purpose technology which ultimately transforms every knowledge-intensive activity, but only after companies pair the technology with the institutional rewiring that’s needed to metabolise them. This requires significant organizational change, process re‑engineering and data governance.

McKinsey shared that some 20% of organizations already report a tangible impact on value creation from genAI. Those companies have done the hard yards fixing processes, tightening data, building skills and should find it easier to scale next year. One such company is BNY Mellon. The bank’s current efficiency gains follow a multi-year restructuring around a “platforms operating model”. Before a single model could be deployed at scale, they had to create an “AI Hub” to standardize data access and digitize core custody workflows. The ROI appeared only after this architectural heavy-lifting was completed. The bank now operates over 100 “digital employees” and has 117 AI solutions in production. They’ve cut unit costs per custody trade by about 5% and per net asset value by 15%. The next 1,000 “digital employees” should be less of a headache.

The best example, though, is JP Morgan, whose boss Jamie Dimon said: “We have shown that for $2 billion of expense, we have about $2 billion of benefit.” This is exactly what we would expect from a productivity J‑curve. With any general‑purpose technology, a small set of early adopters captures gains first, while everyone else is reorienting their processes around the technology. Electricity and information technology followed that pattern; AI is no exception. The difference now is the speed at which the leading edge is moving.

I don’t think this will be a multi‑decadal affair for AI. The rate of successful implementation is higher, and organizations are moving up the learning curve. As we go from “hard” to “less hard” over the next 12-18 months, we should expect an inflection point where value creation rapidly broadens. The plus is that the technology itself will only get better.

Crucially, companies are already spending as if that future value is real. A 2025 survey by Deloitte shows that 85% of organizations increased their AI investment in the past 12 months, and 91% plan to increase it again in the coming year.

One complicating factor in assessing the impact of genAI on firms is the humble mobile phone. Even if their bosses are slow to implement new workflows, employees have already turned to AI – often informally, on personal devices and outside official workflows – which introduces a latent layer of traction inside organisations. This is a confounding factor, and it’s not clear whether this speeds up or slows down enterprise adoption.

On balance, I’d expect this to be the case. In diffusion models inspired by Everett Rogers and popularised by Geoffrey Moore, analysts often treat roughly 15-20% adoption as the point at which a technology begins to cross from early adopters into the early majority1. Once a technology reaches that threshold, adoption typically accelerates as the mainstream follows. We could reasonably expect this share to rise towards 50% over the coming years.

However, 2026 will be a critical check-in. If the industry is still relying on the case studies of JP Morgan, ServiceNow and BNY Mellon rather than a slew of positive productivity celebrations from large American companies, diffusion is taking longer than expected. AI would be well off the pace.

2. Revenue is already growing like software

We estimate that the generative AI sector experienced roughly 230% annual revenue growth in 2025, reaching around $60 billion2.

That puts this wave on par with commercialization of cloud, which took only two years to reach $60 billion in revenue3. The PC took nine years; the internet 13 years4.

More strikingly, the growth rate is not yet slowing. In our estimates, the last quarter’s annualized revenue growth was about 214%, close to the overall rate for the year. The sources are familiar – cloud, enterprise/API usage and consumer apps – but the fastest‑growing segment by far is API, which we expect to have grown nearly 300% in 2025 (compared to ~140% for apps and ~50% for cloud). Coding tools are already a $3 billion business against $157 billion in developer salaries, a massive efficiency gap. Cursor reportedly hit $1 billion ARR by late 2025, the fastest SaaS scale-up ever, while GitHub Copilot generates hundreds of millions in recurring revenue (see my conversation with GitHub CEO Thomas Dohmke). These tools are converting labor costs into high-margin software revenue as they evolve from autocomplete to autonomous agents. The current market size is just the beginning.

Consumer revenues, meanwhile, are expanding as the user base compounds. Monthly active users of frontier chatbots are driving a classic “ARPU ratchet”: modest price increases, higher attach rates for add-ons, and a growing share of users paying for premium tiers. There are structural reasons to expect this to continue, even before AI feels ubiquitous inside firms.

First, the base of adoption is widening. If 2026 brings a wave of verified productivity wins, this trajectory will steepen. More firms should enjoy meaningful results and the surveys should show unambiguously that 25-30% of firms that started pilots are scaling them. As the remaining majority shift from pilots to production, they will push a far greater workload onto a small number of model providers. Revenue can rise even while most firms are still doing the unglamorous integration work; pilots “chew” tokens, but scaling up chews more.

Second, the workloads themselves are getting heavier. A basic chatbot turn might involve a few hundred tokens, but agentic workflows that plan, load tools and spawn sub‑agents can consume tens of thousands. To the user it still feels like “one question,” but under the surface, the token bill – and therefore the revenues – is often 10-40x higher.

Of course, this growth in usage will see token bills rise. And companies may increasingly use model-routers to flip workloads to cheaper models (or cheaper hosts) to manage their bills.

But ultimately, what matters here is the amount consumers and firms are willing to spend on genAI products.

3. The real scaling wall is energy

Energy is the most significant physical constraint on the AI build-out in the US, as I argued in the New York Times back in December. The lead time for new power generation and grid upgrades, often measured in decades, far exceeds the 18-24 months needed to build a data center. The US interconnection queue has a median wait of four to five years for renewable and storage projects to connect to the grid. Some markets report average waiting times as long as 9.2 years.

This is also a problem in Europe. Grid connections face a backlog of seven to ten years in data center hotspots.

For the Chinese, the calculus is different.

Rui Ma points out that “current forecasts through 2030 suggest that China will only need AI-related power equal to 1-5% of the power it added over the past five years, while for the US that figure is 50-70%.”

Because the American grid can’t keep up, data center builders are increasingly opting out and looking for behind-the-meter solutions, such as gas turbines or off-grid solar. Solar is particularly attractive – some Virginia projects can move from land-use approval to commercial operation in only 18 to 24 months. Compute will increasingly be dictated by the availability of stranded energy and the resilience of local grids rather than by proximity to the end user.

These grid limitations cast doubt on the industry’s most ambitious timelines. Last year, some forecasts anticipated 10 GW clusters by 2027. This now appears improbable. In fact, Epoch AI suggests that we would be on track for a one-trillion-dollar cluster based on historic trends by 2030. Assuming such a cluster had a decent business case and there was cash available to fund it, energy and other physical constraints would mean 2035 is a more realistic timeline. As long as it remains dependent exclusively on the scaling paradigm and this timeline slips from 2030 to 2035, capability progress will slow. It’s worth noting, the “slow” is relative here. Even if such a delay materialized, progress might feel fast.