🔮 The horizon for 2024: AI & energy #1

The falling cost of energy; the rise of AI; how firms will respond; who will pay...

Every year, I provide an outlook for the year ahead to help you set expectations in ways that are helpful for the Exponential Age. I wrote a book about this era in 2021, and this newsletter is a weekly practice of analysis and understanding what is going on.

This is the first part of my analysis of the horizon for 2024 and the things you need to care about. A prequel to this is my introduction to how to think about where we are and what lies ahead.

In Part 1 of my horizon scan, I will tackle five themes:

Electrifying everything: Continuing progress in the energy transition

The deepening computing fabric

The corporate AI agenda: How quickly will firms roll out AI?

The business model of AI

Compressing time with scientific AI

⚡️ Electrifying everything

We are at the very peak of fossil fuel use globally. Coal, which powered the Industrial Revolution from the mid-17th century, will be in decline from now on. As we defossilize, technology-driven energy systems (like solar) will guarantee a declining price ceiling for energy, freeing us of the vagaries of commodity-driven energy provision.

Solar power capacity additions are racing ahead. Renewable investment has exceeded fossil fuel investments for six years. Chinese solar panel prices dropped some 40+% this year to as low as 12.2c a watt, strengthening the case for the ongoing deployment of solar.

The rapid improvements in the technoeconomics of solar are making it increasingly appealing—and making forecasts progressively ropey. External forecasters are having to revise their estimates upwards. Our internal models are more bullish than these because we place more weight on learning effects and positive feedback loops.

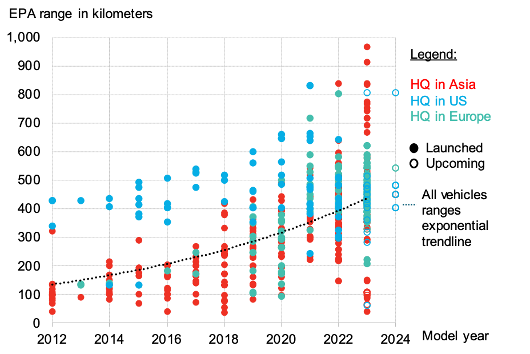

EVs are on a tear with more than 40 million in use. Compared to earlier years, consumers have a choice of a more comprehensive selection of EVs.

The virtuous cycle is taking hold. As the market grows, more firms enter. They compete: offering consumers diversity and innovation. In this case, prices come down, and range — the most critical buying factor for an EV — increases.

Much of this has been helped by the consistent decline in battery pack prices. Cheaper alternatives, like sodium-ion batteries, will contribute to further downward price pressure.

Technology transitions typically follow an S-curve, and since the 20th century, such transitions have typically taken 8-14 years. This was true for the replacement of horses by cars, or Sanger gene sequencing by next-generation sequencing, for feature phones by smartphones, and even quicker for ICE vehicles by EVs in markets such as Norway.

With so much more consumer choice in EVs and the positive feedback loops accelerating (and concomitantly, ICE vehicle ownership and maintenance becoming less attractive) it wouldn’t be unreasonable to see transitions taking less than a decade from the point at which 3-6% of all new cars sold are electric.

The impact of stable and declining electricity prices, divorced from fossil fuel commodity volatility, will be profound. It will allow for longer-term investment decisions in under-electrified sectors, such as heating and industrial processes. These sectors could then benefit from learning curve effects as demand grows. For example, colleagues at the Oxford Martin School reckon that electrolyser costs could drop ten-fold by 2040.

What this means for you: Are you planning for an appropriately rapid transition towards electrification? Have you oriented your business towards an electrified world of stable and declining power prices? Are you sitting on soon-to-be-stranded assets?

⛏️ Boomtime for shovel makers

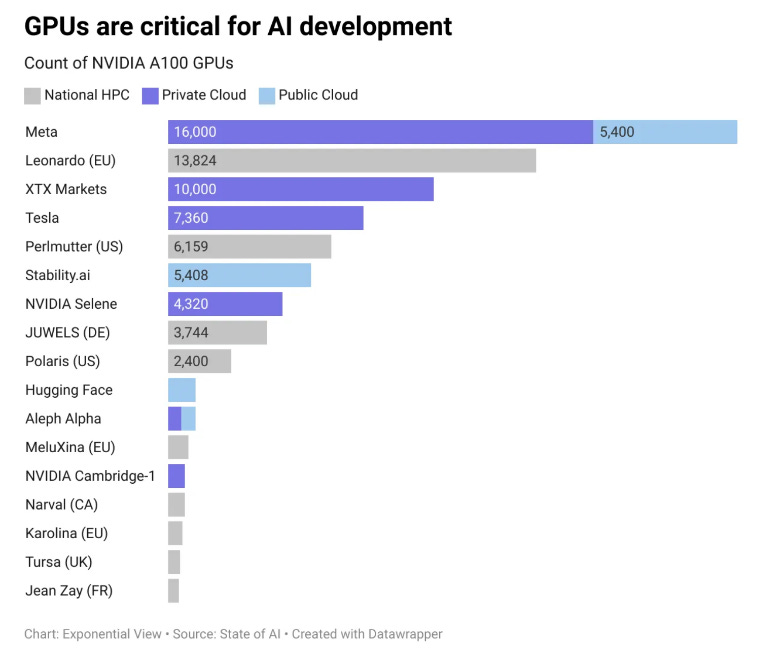

We are also just beginning to deploy AI as infrastructure across our economies. Demand for compute is going to continue to increase dramatically, even as we become more aware of the resources and energy costs of machine learning.

The biggest beneficiary in the past year has been Nvidia, which has leapt into the trillion-dollar club thanks to the little chatbot that could.

Nvidia alone will not be able to meet the demands of this coming society of AI. In data centres, AMD and Intel, and perhaps one or two of the startups, like Cerebras with its gigantic wafers, may have room to run in the short term.

But there are many other places where we’ll start to embed AI: broadly we could consider these the “edge”, devices closer to us where we’ll want inference (or even model updates running locally). Consider cars, which will become mini-AI data centres on wheels. In this segment, Nvidia faces competition from Qualcomm, which has signed tens of billions of dollars for its automotive AI stack, and Intel’s Mobileye. Apple, Qualcomm, and Huawei are the current beneficiaries of devices like phones.

👩🏽💼 The corporate AI agenda

Consider two numbers. Six and ninety-two. These two numbers speak to the pace of corporate adoption of new generative AI tools. In research this summer, Tom Davenport of Babson College surveyed 334 chief digital officers about how they were using generative AI.

Even though the technology has only recently been commercialised, remarkably 6% had one generative AI use case in production deployment. Understand how important 6% as a threshold is. Technologies are not adopted linearly. They go through an S-curve where they experience a period of exponential installation. The curve slows down for the laggards. That ramp has typically started at the 6% level.

The second number to understand is 92%. In November, OpenAI announced that it was supporting 2 million developers, including teams from 92% of the Fortune 500. This is grassroots interest. Roughly over 80% of large firms that do not have generative AI in production deployment have developers playing with OpenAI’s tools.

Davenport’s data doesn’t have a perfect overlap with the Fortune 500, but it is a helpful proxy. The stark gap between CDO’s awareness of employees experimenting at an individual level (less than 30%) and OpenAI’s 92% number. It suggests — and my informal conversations bear this out — that some bosses are unclear about where the frontline developer has moved.

Beyond the technologists, other members of the C-suite are excited by the potential of this new wave of tools. Speaking to several dozen European CFOs earlier this year, the interest in generative AI as a tool for productivity (and, given these were CFOs, cost-cutting) was palpable.

Gen AI has electrified bosses. The C-suite is leading in employee adoption. This certainly wasn’t the case with the Internet in the 1990s when senior executives had to be dragged into the Web kicking and screaming. In 1999, when I was advising a major telco, the then-CEO told me he would never allow customers to pay or even access their bills online. He was right. He left the business a year or so later.

The combination of eagerness from the top and grassroots developer adoption creates a high-octane mix.

In 2024 and beyond, that 6% will inexorably rise towards the 92%. It may take a few years because first it takes time to roll out IT projects, talent is short, prioritisation is challenging. But the groundwork has been laid.

Points to consider: Firms will be under pressure to deliver robust applications on a technology that is, in many cases, not robust — and facing various types of legal challenges. At the same time, more straightforward applications will be available to companies. If these projects succeed in improving productivity, there may be an immediate impact on the rate of new hires or even signs of widespread job cuts. 2023 was too soon to see those impacts. This coming year they might be visible.

💰 The business model of AI: Who is the piper? And who’s paying them?

OpenAI grew from a run rate of $1.3bn in October 2023 to $1.8bn by the end of the year. Anthropic, another LLM peddler, is on course to make $850m in 2024, up from circa $200m a year in 2023. These are small but real numbers in the context of the tech industry.

The New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI for copyright infringement will be a critical test case to help us understand one aspect of this business model.