🫵 You already have an AI agent.

You just haven’t built it yet.

There’s a Mac Mini in my office cabinet, with 64GB of RAM, running macOS Tahoe. It talks to me through WhatsApp, using a dedicated number. WhatsApp is open on my phone or computer all day. Under the hood, it runs OpenClaw, an open-source agent framework that calls Anthropic’s Claude models. It’s mostly Sonnet, sometimes Opus when I need the bigger brain.

This is R Mini Arnold (RMA for short), my first real AI agent.

By “real”, I mean it’s general enough to do a bamboozling array of tasks, and (by and large) it doesn’t forget what it is doing. It picks up where we left off yesterday, runs jobs at 4am while I’m asleep and tells me what happened when I wake up. It manages its own tools. Truth be told, the whole thing is clumsy, max practical utility, no aesthetic. More battlefield surgery than wellness retreat.

In the last 24 hours, I sent 608 messages to RMA. It sent me 3,474 back. Message counts aren’t evidence of leverage, so let me tell you what R Mini Arnold does all day and why it’s been life-changing for me.

And at the end of this essay, I’ll share some of the technical specs of my setup with members of Exponential View. It’ll be enough to replicate and get started.

The boundary of tedium

Every knowledge worker has a boundary of tedium. It’s where a task is too boring or too fiddly for you to do yourself, but too complex or too specific to easily hand off to someone else.

Below the line, you just do it, grumbling all the way. Obvious things like grooming the CRM, file management, email, follow-ups, and meeting prep clearly sit inside this boundary. So too does chasing down a piece of information you know exists somewhere in your notes. Reorganizing your notes because they have drifted into chaos while you were busy with “real” work. Checking a contract.

The “glamorous” stuff in any job sits on top of a vast administrative substrate, and if the substrate isn’t maintained, the glamorous stuff doesn’t move forward either. It’s exactly this boundary of tedium where R Mini Arnold operates right now – at the frontier of what I can now be bothered to delegate.

But each of us has a different idea of the boundary of tedium. People who’ve worked with me know that I find a lot tedious.

A presentation I needed to put together would have taken me sixteen to eighteen hours (after my team’s work). With RMA, it took me an hour and a half. Deciding the flow, pulling data, and sequencing the arguments during my practice run, that’s mostly assembly work. Fiddly enough that I’d not brief someone else to do it but equally boring enough that I’d leave it until 2am. When it was done, I just sat there. Sixteen hours of work from ninety minutes.

Then RMA helped me build Orbit, a personal CRM. It pulls from Gmail and WhatsApp, cross-references who I’ve been talking to with what I’ve been writing about, and nudges me on who to reach out to – for a dinner, an intro, a collaboration. I still check entries by hand. But Orbit had been sitting in my someday-maybe pile for many months. It’s built, and more importantly, filled with several hundred contacts, how I know them, when I last spoke to them, and which of them might benefit from knowing each other. I really do use it, my team uses it, and RMA uses it.

RMA presents its reports to me in Markdown files, which get dumped into Obsidian, a note-taking app. My personal knowledge base lives in that Obsidian vault. It is also connected to my Granola and a few other inputs that I use for meetings, reading and scheduling. At one point, well, about two days in, it had become a mess. Hundreds of notes were filed badly or not at all. I told RMA to sort it out, to find a taxonomy, reorganize everything and keep it tidy. It moved dozens of files and imposed conventions. The first time it did it, things were chaotic. It took two more iterations to get it right.

I admit none of this is heroic, and that’s the point. A sceptic might read this list and say: you built an elaborate system to do filing? Yes. Because filing is my least favourite part of the job. And the filing wasn’t getting done.

The cost of explaining what I want dropped by an order of magnitude. The boundary of tedium moved, and a vast category of work that used to sit in the “too annoying to delegate, too boring to do” zone crossed to the other side.

What 179 failures built

It’s not all roses in 100-million-token land. Remember the battlefield clinic.

There have been 179 unresolved failures in six days. One of my apps, Canvas, now fails 100% of the time. The first email drafts sounded like they were fresh from an LLM – I still rewrite about 40% of them. The technical setup is often nightmarish.1

But RMA also tells me we’ve had 32 documented corrections, which produced 146 learned patterns, encoded in a file called SOUL.md. Those mistakes might not happen again.

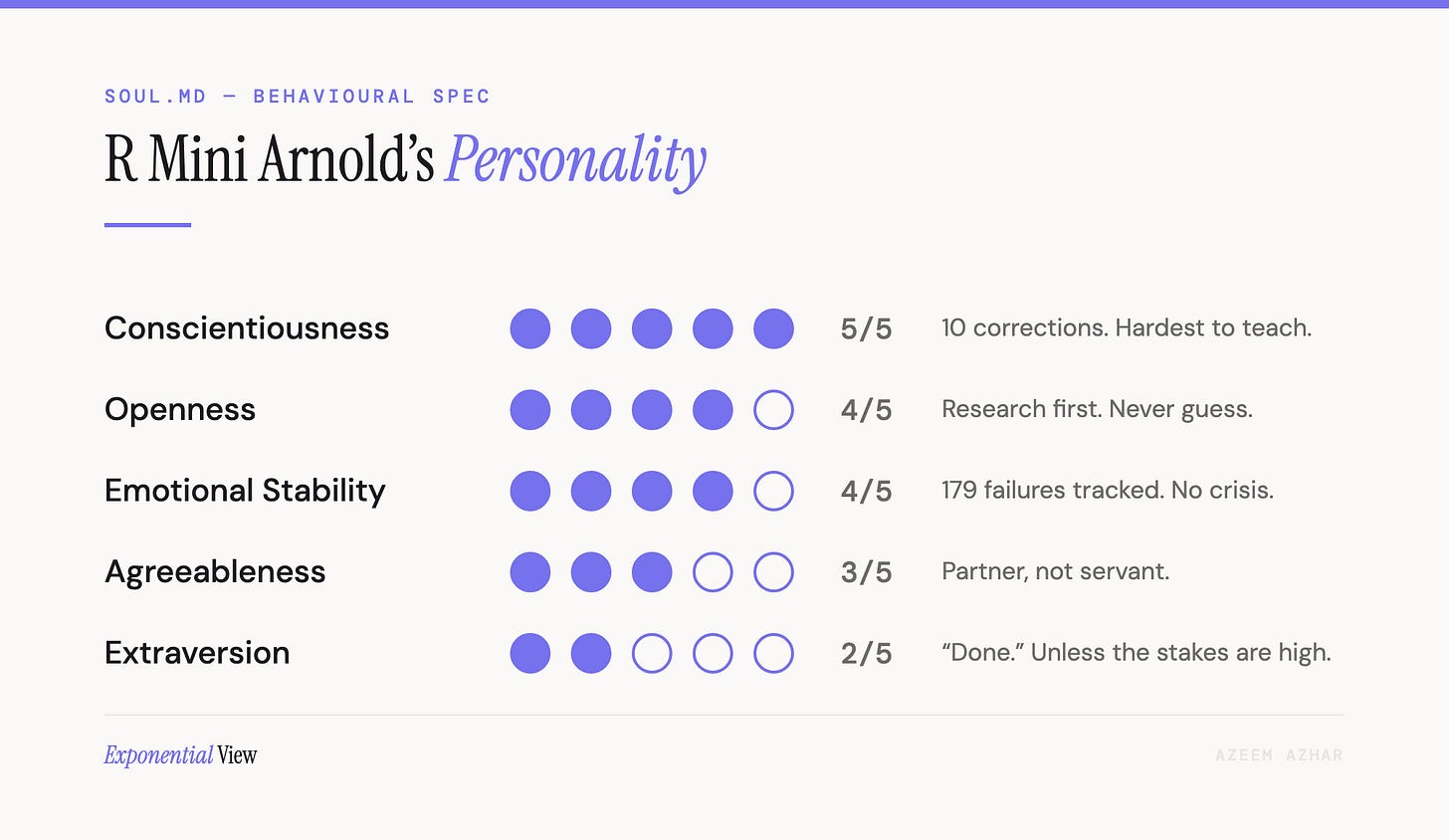

I had RMA manage two agents that did independent research on the best academic papers on getting LLM agents to behave usefully. The most effective technique was, apparently, encoding personality using the Big Five traits. So I asked RMA to analyze our interactions – the corrections, the work patterns, the kind of tasks I delegate – and recommend the trait levels it should operate at. The agent designed its own personality spec, based on evidence of what I need.

Here’s what we landed on: