🔮 Our collective brain is ageing. What does it mean for our civilisation?

An older world can be good, but only if we make it so.

Hi,

I am on holiday so I asked EV member, Gianni Giacomelli, to challenge us with an unorthodox idea. He’s delivered. In today’s essay, Gianni gives a new take on demographic shifts by asking how might an ageing population affect our overall collective intelligence.

Gianni argues that the several co-occurring factors associated with an ageing population will dramatically impact the way we think, innovate and behave collectively. So, what reforms will we need?

I want to stress how important a question this is. So please do engage with Gianni and other members in the comments — and thank him by restacking this post on Substack.

Cheers,

Azeem

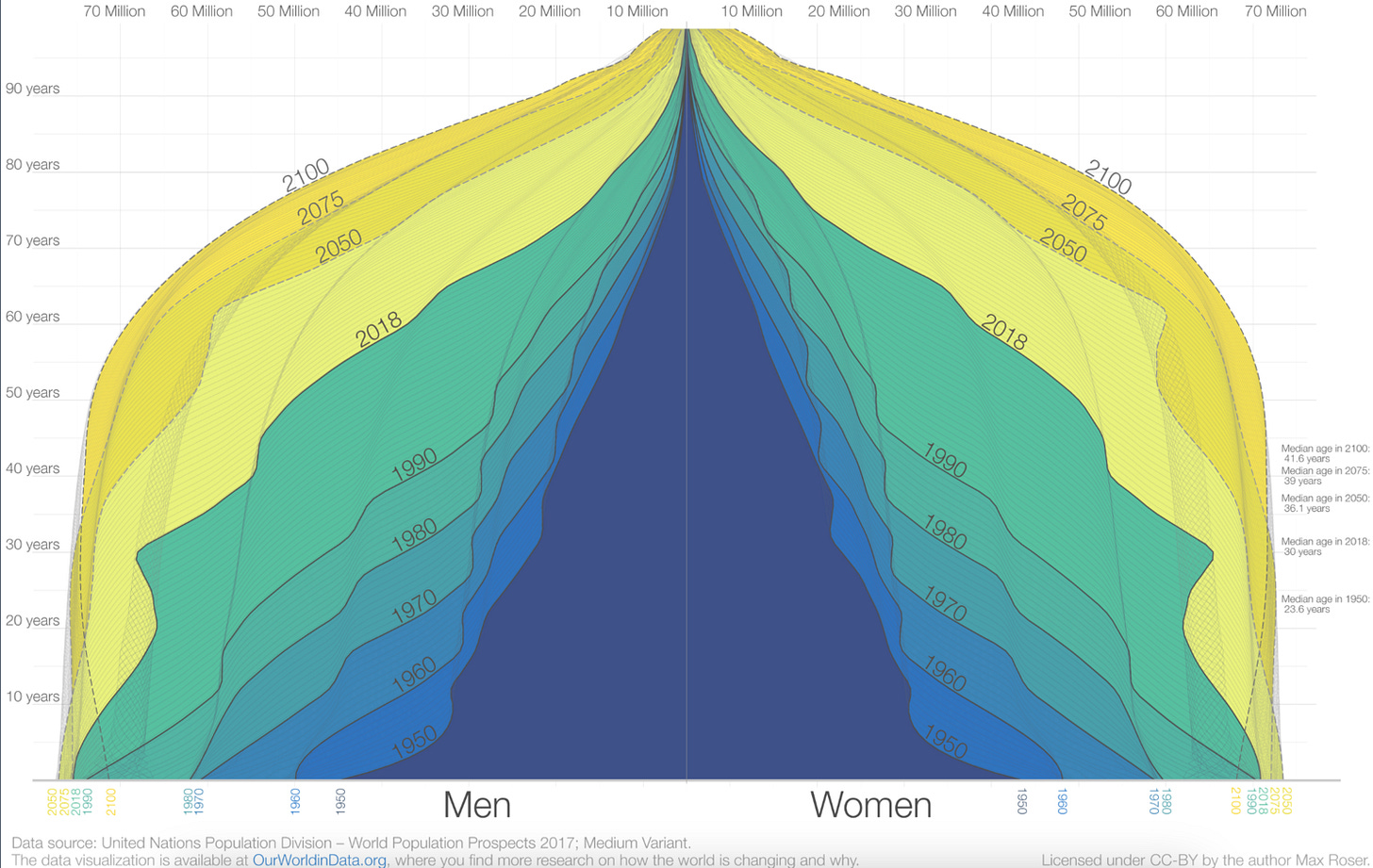

The world is heading into a future with many more older people. The impact on economies can be devastating1, precisely when we need resources to address large challenges such as climate change.

Is demography destiny, as some (quite a few) suggest? Are our demographics shifting from the “progress pyramids” to “domes of doom”? Are fertility policies (whose impact is debatable) the only way to address this problem?

I will examine the problem through a lens of collectively intelligent systems, and highlight potential challenges and solutions.

Our civilisation’s collective brain—one instance of what Thomas Malone termed a “supermind”—relies, in the words of sociobiologist Edward Wilson, on the interplay of three elements: palaeolithic brains with their inherent emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. I want us to look at how the collective brain could change in an ageing world given that…

Our individual brains age and consequently their capabilities and incentives change,

Many of our institutions’ evolution doesn’t keep pace and is misaligned with the majority of citizens and people (though possibly not the short-term expressed will of the majority of the voters or believers),

And our technological innovation (AI and others) has the potential to improve the efficient frontier and total factor productivity. This would bring economic prosperity, but their penetration and impact on established economic systems are still partially unpredictable.

By examining this interplay of challenges, capabilities, and incentives—both individual and collective—we can better understand how our ageing world might reshape our collective brain, and what to do about it.

Individual brains

As individuals age, their cognitive abilities change and in some areas degrade, especially with regard to the absorption and processing of new knowledge.

Granted, ageing today is cognitively different compared to the past, as people stay fit for longer. And yet, given the longer lifespan and the incidence of age-related conditions like dementia, we will see an unprecedented proportion of the total population with somewhat degraded cognitive abilities. Longer lifespans spent in retirement aren’t conducive to people consistently keeping their minds challenged and keeping cognitive decline at bay.

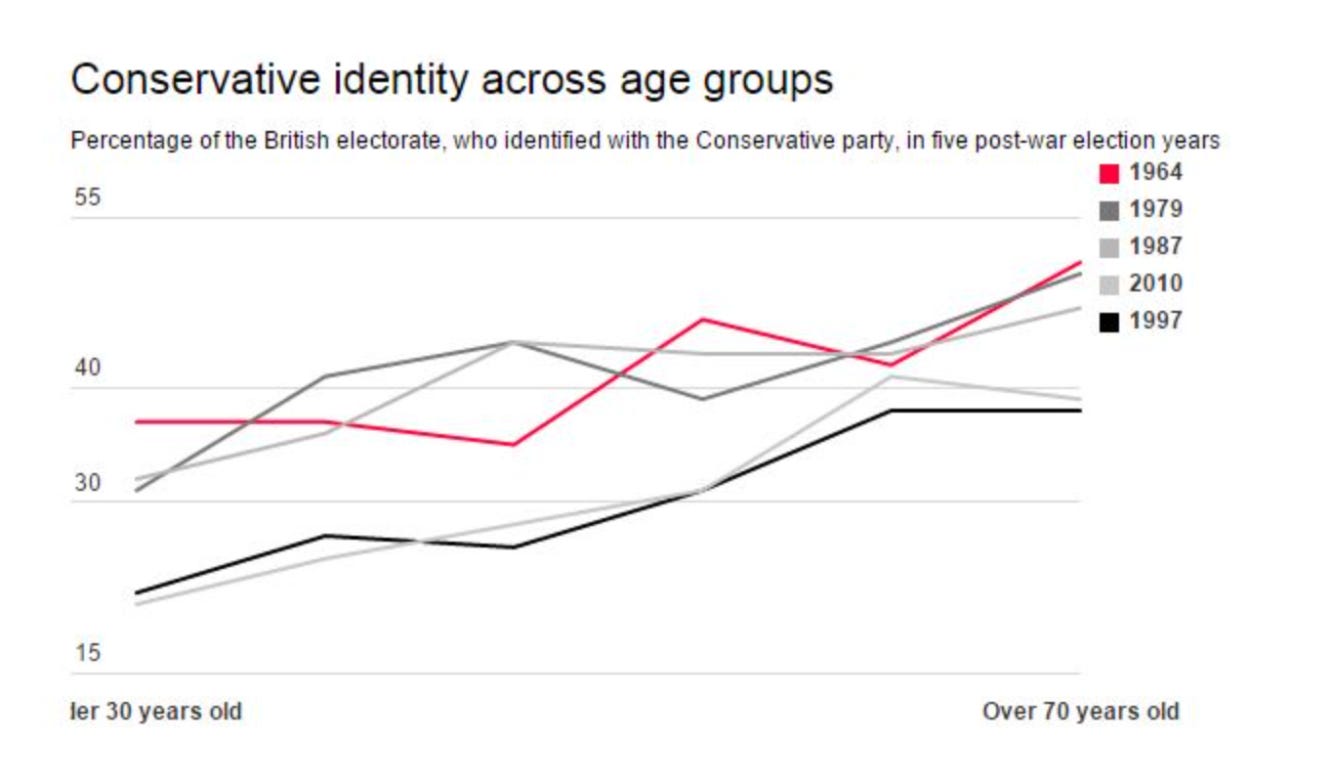

The conservative tide

Ageing societies tend to shift towards more conservative positions, especially during economic and social shocks. This rightward drift would be balanced in a typical democratic system if younger generations participated in public governance as actively as older cohorts. However, youth underrepresentation in politics amplifies the conservative shift. For instance, in the US, both politicians and voters skew older, influencing even presidential debates. Many older politicians’ core values were shaped during their formative years in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, they sometimes focus on battles that originated in that era, potentially overlooking more current concerns. This fuels the quest for finding enemies and fighting wars that are no longer a priority, and are framed in ways that aren’t contemporary anymore (one can see geopolitics and identity politics through that lens, too). European politicians are getting slightly younger, but young voters are still underrepresented on the ballot, and their voice is heard less. Since younger people typically do not engage as actively in these processes, and their networks (which are often critical for nominations to important roles) are comparatively underdeveloped, there is a risk that governance becomes more conservative than the society as a whole.

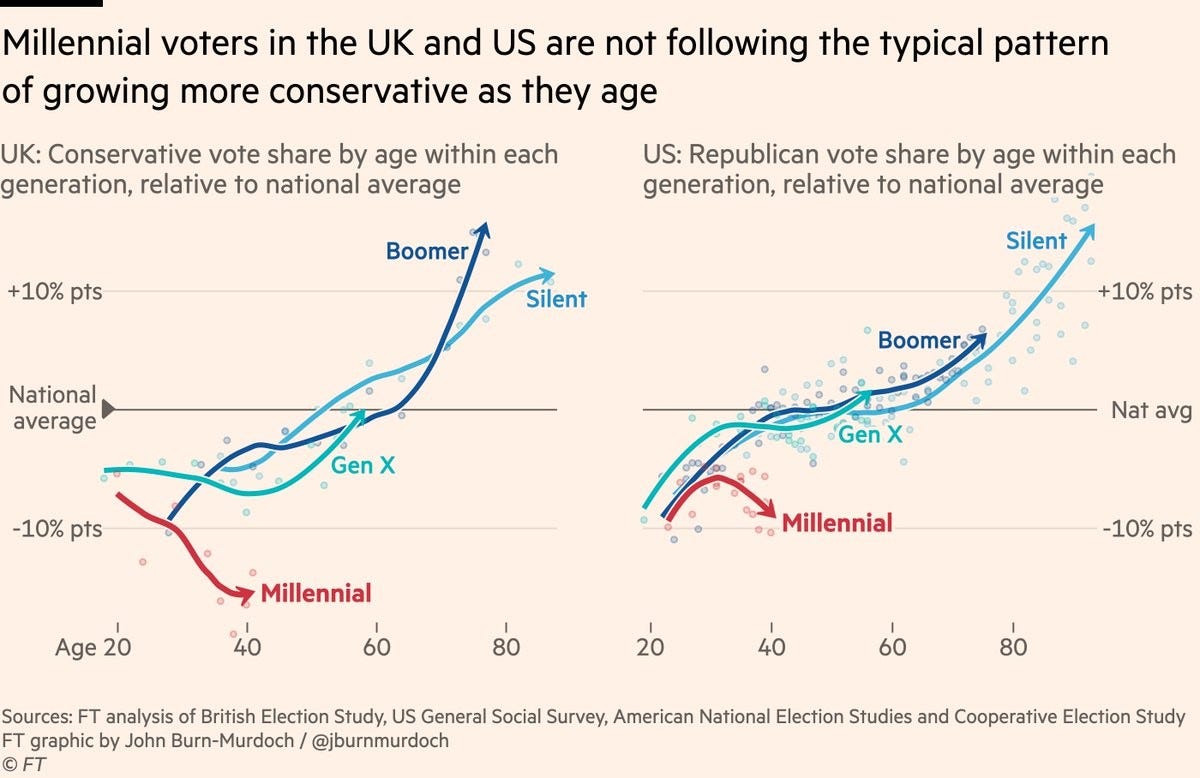

Recent studies indicate that Millennials in the US and UK are not following the traditional pattern of becoming more conservative with age. However, due to the current demographic structure in developed economies, where older generations still outnumber younger ones, Millennials may not have sufficient influence to counteract the overall conservative shift in societal values for some time.

This effect is mediated by institutions - democratic or not.

As traditional liberal parties struggle to adapt to changing social narratives, some fringe political views may gain traction, partly amplified by social media echo chambers. This polarisation can increase societal tensions and conflict. And while some research indicates that older societies tend to wage war less because their ability to deploy troops is diminished, demographics could lead to perverse short-term dynamics in countries on the verge of ageing (Russia being one), and still leave the door open to autonomous-weapon warfare.

Impact on the markets

The markets, with their complex, decentralised, and dynamic decision-making processes for the allocation of resources, are another part of our collective brain. Organisational leadership has aged, for instance. Ageing societies also experience shifts in money, both private and public. As an example, housing is one the largest budget items in people’s lives, but real estate taxation, and zoning laws, protect current homeowners (who skew older), contributing to inequalities. There is also the potential for stock market behaviour to change over time as older generations, who own a significant amount of wealth, burn through their savings - though the net effect is not fully clear yet.

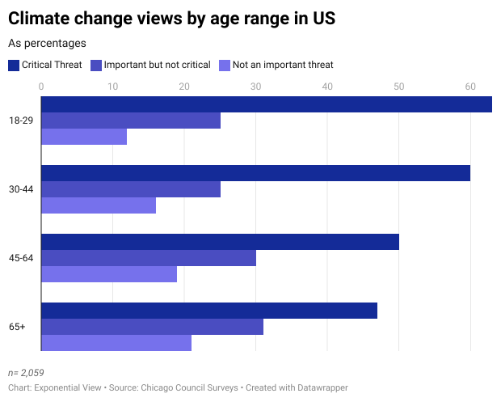

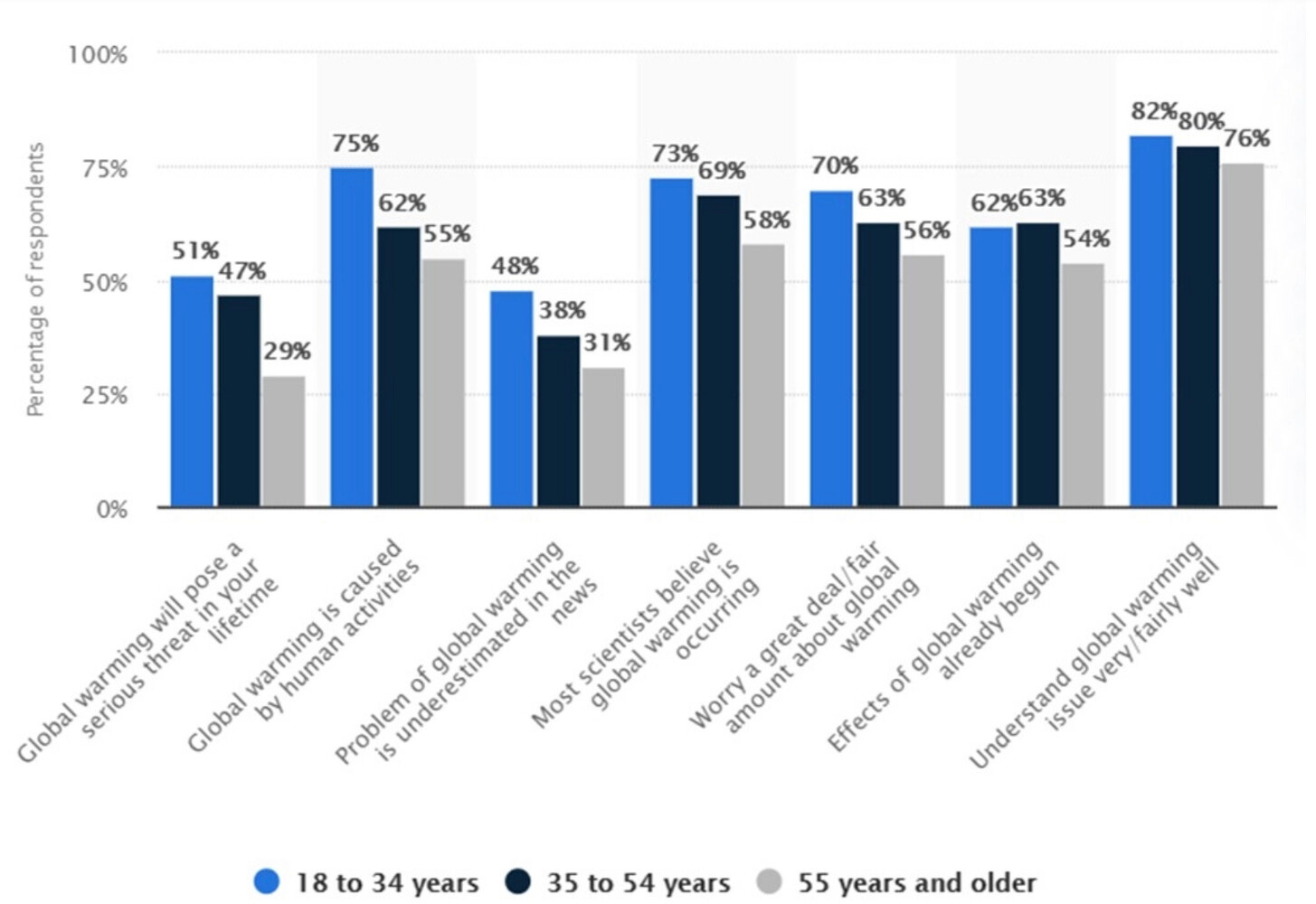

And naturally, money will be needed for the climate and energy transitions. According to the IMF, as noted by The Economist, “rich countries will spend 21% of GDP a year on old folk by 2050, up from 16% in 2015. A quarter of that will go on pensions. The rest will be required for health- and social care provisions”. Here, once more, the generational divide that drives policymaking is visible, and not just led by hard science and economics. The example below is from the US…

…and these from the UK.

The perspective of European and Asian countries is less polarised, but the trend is the same, especially when it comes to the impetus for action.

Innovation risk

Finally, and crucially, ageing societies can see a change in how they innovate. Starting with (ageing) academic leadership - crucial for inventions - where incentives are stacked in favour of academics going deeper and for more years into their narrow field rather than looking across disciplines. The charts below illustrate for instance how papers referenced by older academics are on average older and their research is less likely to disrupt the state of science and more likely to criticise emerging work.

This, combined with the burden of knowledge and specialisation, can slow down disruptive innovation and breakthroughs. The chart below shows the effect of age on the novelty of academic research over the life of researchers, and over time.

Two famous quotes encapsulate the potential problem. Arthur C. Clarke quipped that “[w]hen a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong”. Max Planck famously lamented that science often shifts paradigms only when old academics die.2

Innovation is not just invention though. An older population might mean slower uptake of new ways of doing important things. Landmass use for instance will be crucial in our climate transition, but in Europe, the region where environmental policies are politically least controversial, the average farmer’s age is about 60 (and only 10% are below 40). More money for the older people might mean less money for the young, their education, and the support they need to credibly enter the workforce and change work practices, with a potential impact on the speed of adoption of innovation. In another example, energy and transportation senior executives in incumbent Western companies might feel that, if they delay things just enough, they might be able to juice the previous investments in older technology (fossil fuel generation or ICE, for instance) and retire without needing to push through hard changes that could jeopardise their financial profits in the short term. The possible onslaught brought about by Chinese EV companies, whose economies of scale and Wright curves have driven cost reduction can now only be fought with import tariffs, shows the risk of misreading the time it takes to realize the benefits of innovation. In general, the average age and time-to-retirement of senior executives might skew decision-making in companies, especially publicly listed ones, although the effect may not be linear and some older leadership teams might indeed focus on leaving a lasting legacy.

Trying new things also requires a certain amount of risk-taking. Judging from the data in the chart below, and despite all caveats required in such analyses, there is reason to believe that ageing, wealthier societies see progress as more of a half-empty glass than they did in the past.

Clearly, we cannot allow a small minority of people, who have the requisite tech capabilities and skew much younger, to work alone on significant technological innovations with the potential to create significant risk to everyone. There’s more than a grain of truth in the claim that Silicon Valley’s youthful (immature?) ethics is an insufficient moral compass in these times. But the option of stifling the right type of innovation is not viable either. An older population might lose touch with the younger minority able to drive innovation fast, which would be a dangerous mistake.