🔮 Europe‘s power problem

I spent time with Europe’s electricity execs this week and I left stunned by what I heard (or rather didn’t hear)

In 1878, the Avenue de l’Opéra in Paris became one of the first major urban streets to be illuminated by electric arc lighting. The transformation was visually striking and socially disorienting – and would forever change how Parisians move through their city.

Other European capitals took note. Germany, especially under Bismarck’s leadership, was in a period of rapid industrialisation and keen to avoid falling behind. Within a year, Berlin had its first experimental electric street lighting. Within four years, Berlin had operational power stations supplying electricity for streetlights and tramways. And within few more years, Berlin launched one of the first long-distance transmission lines, which became a global benchmark.

Today’s equivalent “streetlamp” is the GPU rack. Just as lighting was once the signature use-case that pulled electricity into factories and cities, AI is now the load that reshapes grids, economies and infrastructure priorities.

And Europe is falling behind. I spent a few hours with executives involved in the European electricity sector earlier this week. I was shocked by the lack of urgency. It’s railway planners in the age of jet engines – still optimising track gauges while the skies fill with air traffic.

After the conversations I had this week, I felt Europe might just cede the next stage of industrialisation – the exponential economy – to those building faster and more abundant power infrastructure elsewhere. Decarbonisation, not abundant energy, was the mantra. Both, of course, are possible over time.

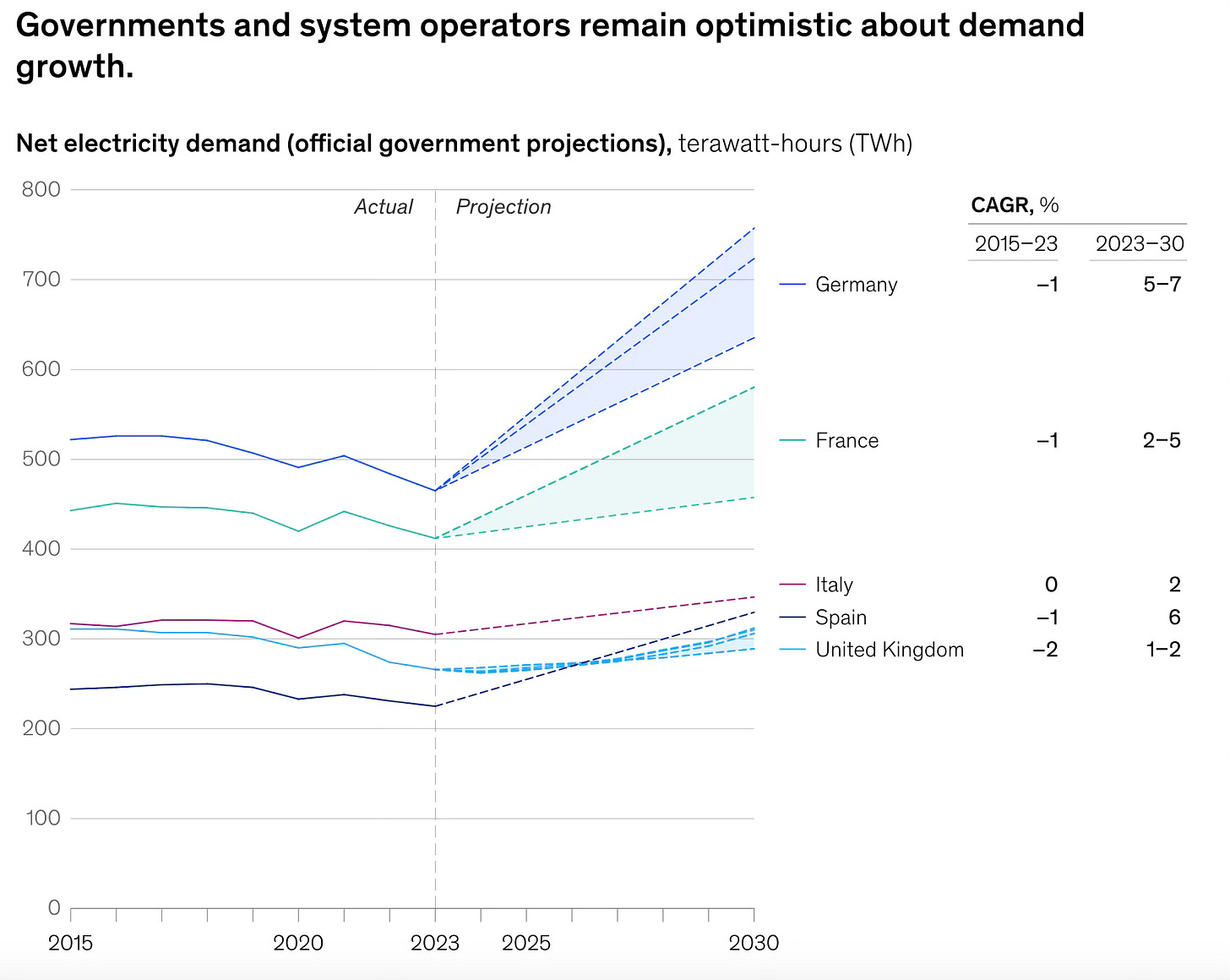

Generative models are multiplying, heat pumps are displacing boilers, electric cars outnumber diesels on many dealership forecourts. Yet Europe’s wires still carry roughly the same amount of electricity they did a decade ago. That tension is about to snap.

Negawatts won’t get us far

For twenty years, Brussels preached “negawatts”: use less, waste less, decarbonize through efficiency. It worked1; until everything that is valuable for economies over the next half-century started plugging in.

In transport, one in four new cars sold across Europe this spring carried a battery rather than a fuel tank; plugins now command 26% of the market and are still climbing. Heating is following: more than 2 million heat pumps were installed last year, despite a market slowdown, taking the cumulative stock past 26 million units.

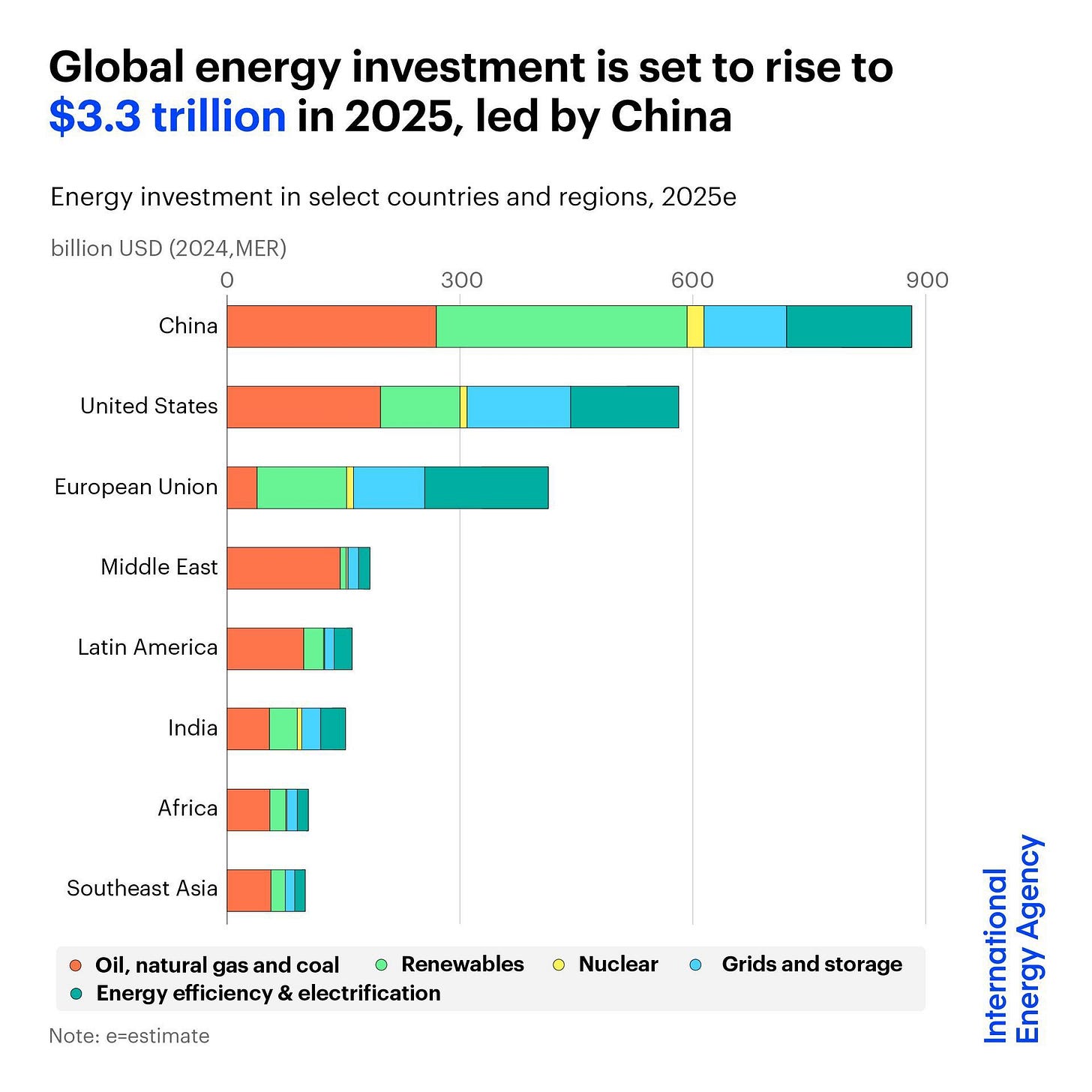

Then comes artificial intelligence. Global data-centre demand will more than double to 945 TWh by 2030, driven largely by AI workloads. Goldman Sachs reckons that these loads could increase European power demands by 10-15% over the next decade.

Add those curves together and continental system operators are modelling annual power-demand growth of up to 7% through 2030, the steepest increase since post-war reconstruction.

Compute will cross borders

Europe’s energy story has to switch from efficiency to growth. Fast. If Europe wants European values to have a place on the world stage, it’s vital to stay in the game.

The recent US-UAE deal green-lit a 5 GW AI campus in Abu Dhabi and access to 500,000 Nvidia chips per year, all within 100 milliseconds round-trip latency of most European capitals. Compute can cross borders far more easily than electrons can.