💨 Climate capitalism: How market forces and policies align

Orsted, a case study

Hi,

Today we have a special guest essay by Akshat Rathi, a senior reporter for Bloomberg Green1 and the host of the climate-solutions podcast Zero. Akshat’s new book Climate Capitalism comes out in October (I highly recommend you pre-order) — so I asked Akshat to share with us how a successful alignment between market forces, technology, and policy can be achieved to form effective and scalable climate solutions. His insights are not just hopeful; they’re instrumental in understanding the actionable steps we can take.

🙌 Thank Akshat for sharing his exponential view with us by forwarding this email and sharing it with your network.

Enjoy!

Azeem

Climate capitalism

By Akshat Rathi

Barely a day goes by when news headlines do not feature some disastrous extreme weather event made more extreme by climate change. And because the laws of the physical world are immutable, we can be certain it’s going to get worse as we continue to burn fossil fuels and grow the load of greenhouse gases that heat the planet.

That bad news understandably fuels climate anxiety. Tackling climate change requires reaching zero emissions within decades. Achieving it will mean upending the energy system that has deep links to global geopolitics and economics, as Russia’s attack on Ukraine has made plain. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed and despair.

That’s why I wrote Climate Capitalism because there’s also good news all around us. Every sector of the economy and every country on the planet that I’ve had the privilege to explore over the past decade has people working on climate solutions. Crucially, in many places these are now working at scale.

And all that is already making a difference. Since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, the worst-case scenario for global warming has been toned down from more than 4°C to less than 3°C. Pretty bad still, but not quite the hellscape it could have been. And if governments meet the goals they have set so far, we could keep heating below 2°C—meeting the less ambitious of two goals set in Paris.

Given the increased support for climate action globally, there’s no reason to believe that government ambition has reached its peak yet.

That progress is built on success stories. Some of these are tied to exponential technologies that Azeem writes about in this newsletter often: solar, wind, batteries, electric cars and so on. But how exactly many of them went exponential is not well understood. In addition, these technologies needed systemic developments to succeed, including those in finance, laws and international institutions.

In Climate Capitalism I use examples from around the world to show what it takes to successfully deploy climate solutions. I build a framework for how these solutions can be scaled everywhere in the world. Along the way, I bust some myths, explains how exactly a solar panel works, reveal how Bill Gates got to funding climate solutions, and a lot more. Let’s jump into one powerful case study.

A case study in transformation

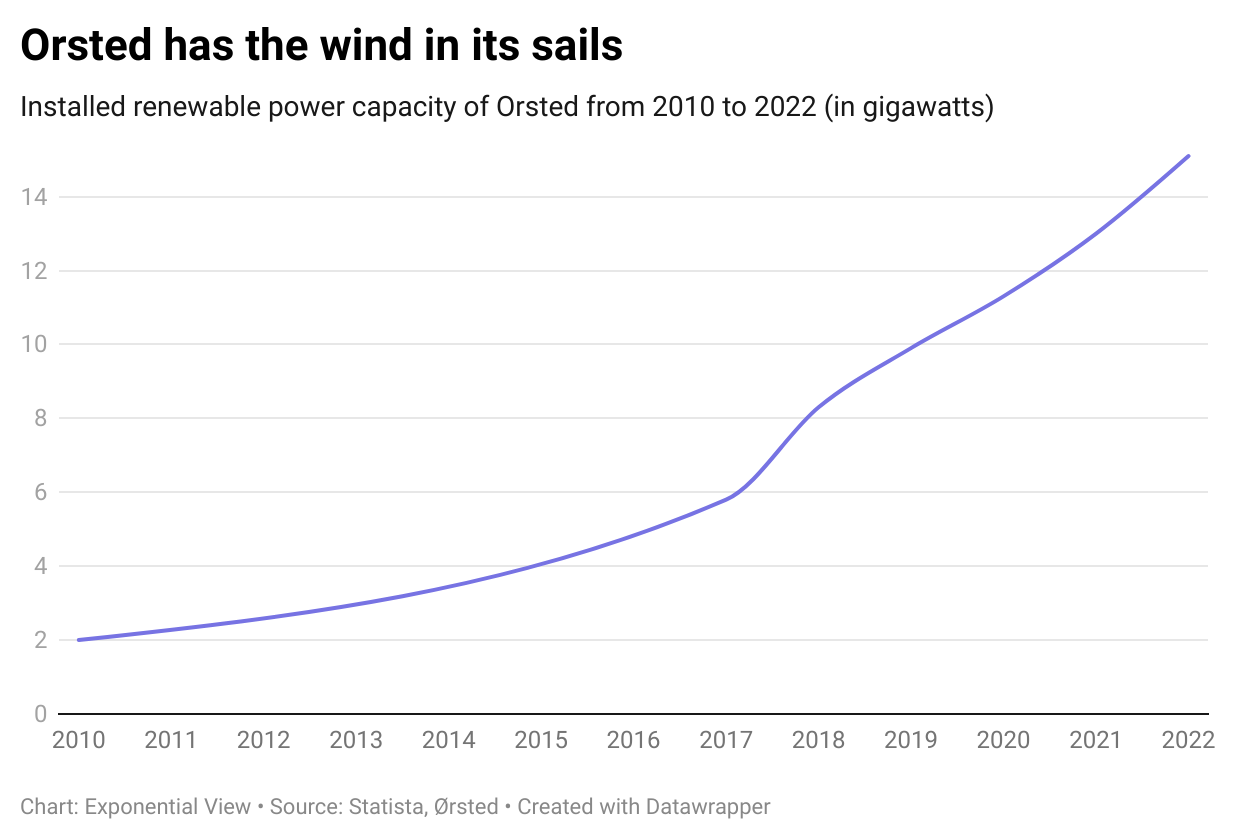

Let’s consider the example of Orsted. If you’ve heard the name, you probably know it’s the world’s largest developer of offshore wind power. What you may not know is that the company used to be called DONG, which stood for Danish Oil and Natural Gas. That transformation from an oil and gas company to a renewable energy giant is a case study at management schools about how careful planning and foresight can pay off. It shows exactly what companies must to do in the climate era.

It’s only half the truth. Much of how Orsted came to be is down to Danish government’s policy trials as the country navigated a changing energy landscape.

The story starts, as many energy transition tales do, during the 1973 oil crisis. Denmark was among the worst hit countries after Arabian oil-exporting countries announced an embargo in response to Danish support for Israel. The small European country got 90% of its energy from oil and 90% of that oil was imported from the Middle East. Lack of access to the fuel brought the country to its knees.

“It was a very dramatic wake-up call for Danish society. Politicians said ‘never again’,” recalls Ander Eldrup living through that period. Eldrup would go on to work for the Danish government and then become CEO of DONG.

Over the next two decades, Denmark took big steps to do three things: (1) diversify the types of fuels it consumed, (2) diversify the sources from where it got those fuels, and (3) reduce energy consumption wherever possible. Each of those steps were imagined by the government through the help of the newly created Danish Energy Agency, but the execution came down to private companies, state-owned companies, and local governments.

State-owned DONG was at the helm of trying to exploit the newly found oil and gas in the Danish North Sea.

Private companies Grundfos, Danfoss, Velux, and Rockwool were at the forefront of deploying energy-efficiency technologies. Many municipality-owned utilities were involved in switching power plants from burning oil to coal, gas, biomass and waste instead. Those utilities were also required to map out demand for heating in the cold European country and make plans for meeting that demand by burning gas or through district heating. All of this came with taxes on energy use first on oil and electricity, then on coal, carbon dioxide, and natural gas.

By 1990, much of these investments began to pay off. The share of buildings burning gas rose to 10% from zero, while those using district heating doubled to 40%.

Neighbouring Sweden embraced nuclear power, but Danes were opposed. Instead, a grassroot movement was formed that wanted to exploit wind power. A group of Danish students built Tvindkraft in 1978—at 53 meters tall and capable of producing 900 kW of electricity—it remains the longest-operating wind turbine in the world. That inspired a local inventor named Henrik Stiesdal and a local maker of cranes named Vestas to get serious about creating an industry out of generating wind power. These were supported through small but steady grants and policies from the Danish government to build onshore windfarms and then offshore windfarms as early as the 1990s.

DONG’s transformation from being a producer of fossil fuels to generating wind power came as a response to two major crises.