We normally reserve our Chartpacks for the paying members of Exponential View, but we want to foster a wider debate on this topic given its importance for a wide range of issues, including the future of our democracies. We have opened Part 1 of our Chartpack on Industrial Policy to all, so please feel free to share widely and discuss in the comments.

Industrial policy is making a comeback. Once a key force in growing economies after World War II, it’s gaining popularity again. A mix of reasons drives this revival, including strengthening industrial competitiveness, securing vulnerable supply chains, technological competition with China, and fighting climate change.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll explore, first, the reasons behind the shift towards industrial policy (Part 1), and second, evaluating their effectiveness in addressing current challenges (Part 2, coming out next week). While our analysis centres on the US, the conclusions and implications are globally relevant.

In this first part, I will cover:

Brief overview of industrial policy’s comeback in the current economic context.

The historical significance of public R&D in technological breakthroughs — and whether the gap can be filled by industry and VC.

The concept of catalytic government — and who’s already on the move.

The great offshoring

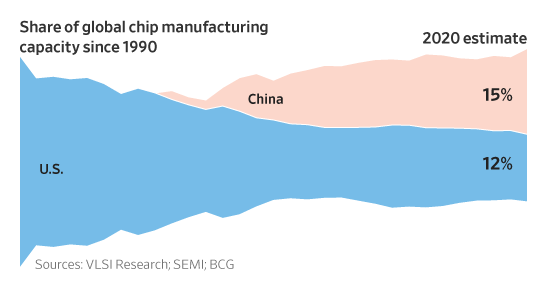

One of the main reasons the US is returning to industrial policy is the significant loss incurred from offshoring manufacturing, partly a consequence of abandoning such policies in the late 70’s. This led to a significant decline in local manufacturing expertise, particularly evident in the semiconductor sector, once the cornerstone of Silicon Valley’s growth.

The US Government nurtured this sector by subsidising development and providing demand with defence contracts. However, they began pulling back in the 90’s. In contrast, East Asian governments escalated their support for their manufacturing industries.

This shift, along with the rise of a skilled engineering workforce outside the US, dispersed the semiconductor supply chain globally to enhance cost-effectiveness. This might seem benign in a peaceful world, but increasing global conflicts are raising the risks associated with not being able to produce one’s own strategic assets, like chips.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought to light the consequences of such global dependencies. In the US, the abrupt halt of automobile production due to semiconductor shortages revealed the vulnerability of international supply chains. This crisis was a wake-up call. It made countries think differently about outsourcing essential manufacturing capabilities.

Public research funds shrink

Another key change is the decreased public R&D funding over recent decades. Public funding served as the backbone for breakthrough technologies like nuclear power, the internet, GPS, and semiconductors. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) reveals that China leads in 37 out of 44 critical technologies, highlighting that the US was caught sleeping at the wheel.

Industry has tried to fill public R&D’s shoes, but there are important differences that mean it can’t completely replace it. Deep tech venture capital has been an incredibly relevant player, as we showcased in the Chartpack about the rise of defense tech. By enabling commercial enterprises to engage in extended R&D, it helps nurture and potentially commercialise unproven, promising, technologies such as nuclear fusion. Yet, industry struggles to do research just for learning, without expecting a return in a short few years.

Public R&D can fund big, long-term and risky research. Industry R&D, focused on commercialisation, cannot afford to do so. The loss here is the early, basic research that later commercial products are built on, like the Internet. DARPA in the US bears responsibility for most of our digital infrastructure, exemplifying public R&D’s unique contributions.1 Increasing public support for R&D is crucial for the US to maintain technological competitiveness with China.

Subsidies can be governments’ industry steroids

We mustn’t get gridlocked into black-and-white thinking. Contrary to popular belief, the government can play a role in commercialisation. New technologies often have small initial markets and high risks, which can hinder initial investment in the tech. Subsidies can be effective in markets that require extra incentives to accelerate learning effects.2 Such interventions can hasten market development by boosting adoption, which systematically lowers the price through learning. However, they should be promptly scaled back once the market begins to sustain itself.

The development of Germany’s solar energy industry is a stellar example. The German government’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG), which favoured renewables in the energy system and established a minimum price for such electricity, not only spurred technological advancements in solar energy but also cultivated a robust market, propelling Germany to the forefront of the renewable energy transition.

Crucially, subsidisation under the EEG was instrumental in leveraging learning effects, as it provided the necessary financial support and market stability for the industry to experiment, innovate, and achieve economies of scale, thereby driving down costs and enhancing efficiency3.

It’s clear why government help is crucial for dealing with the climate crisis. Governments can close the gap between innovation and the market, speeding up the introduction of important technologies for a sustainable future.

We’re now at a point of realisation that government intervention to some degree is needed. The loss of America’s strategic manufacturing capabilities and the urgent need to develop new technologies to deal with the climate transition has led to an entirely different way of thinking about industrial policy. In December, Azeem posited that governments are increasingly intervening to foster growth and innovation - something he calls the catalytic government. They are doing this by defining key areas of focus, such as environmental sustainability and national security, via industrial policy.

In Part 2, published next Wednesday, we’ll look at how the United States is revisiting industrial policies to deal with these issues. We’ll see that while this offers some direction, it’s not without its challenges.

Of course, government interventions are not immune to failure. Consider, for instance, the problematic outcomes of US subsidies in agriculture, fishing and fossil fuels.

For more details on this process, we recommend Gregory Nemet’s book, How Solar Became Cheap.

The push for industrial policy is welcome and this chart pack makes it easier to explain to people. As far as I know there is always a missing piece in industrial policy. For example, 6 or the 7 Darpa technologies are the foundation of the massive valuation gain for Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce, Airbnb, DropBox, Amazon, etc. over the past 20 years. A thousand years ago, when land was the foundation of wealth, taxes were collected on that wealth. Every year.

We need to do the same. And for those who celebrate balanced budgets, we get those too.

Great piece. I wonder if it is worth noting that the same needs exist for R&D on faster and more universally effective education and training technologies. In many sectors, from power grid operators to company trainers, higher competence and great numbers of trained personnel are needed.