In my commentary this week, I look at the insightful research note from Goldman Sachs, titled “The Potentially Large Effect of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth”, in which the authors explore the labour market's future.1

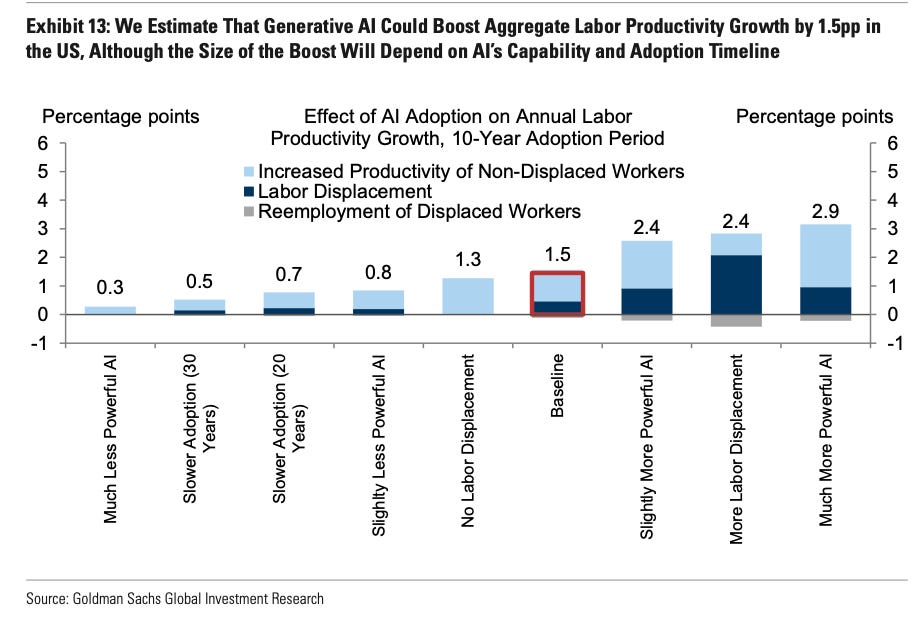

The study posits that global productivity could see an impressive uptick, ultimately boosting global GDP by 7%. In the U.S., economic growth could leap from the anaemic range of 1% to 1.5% to a more robust 2.5% to 3%, reminiscent of the booming 1950s and 60s.

The research highlights that AI automation affects two-thirds of U.S. occupations to varying degrees. A significant portion of these jobs could see substantial replacement due to automation. The researchers propose that jobs with 50% or more of their tasks automated are at risk, while those with 10-49% automation will see AI complement human efforts.