✨ This Nobel Prize matters

Edit: The original version didn’t acknowledge David Baker as the third recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his remarkable contributions to computational protein design.

This year’s Nobel Prize selections have been particularly intriguing. While I’m currently traveling and unable to provide extensive commentary, I’d like to share an essay I sent to members a month ago. It offers context for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This Prize shows growing belief that AI will transform the world in which we live.

Professors John Jumper and Demis Hassabis are jointly receiving the Nobel Prize for their work using AI to predict the structure of nearly all known proteins. They share the award with computational biologist David Baker whose work has deepened our understanding of proteins. AlphaFold exemplifies how AI can help us tackle one of humanity’s most pressing challenges: overcoming the limits to our knowledge.

There are questions, as there often are, about the Prize in Physics. I suppose it’s a stretch to say the work in neural nets is physics but perhaps this is the Prize committee putting a dent in the universe because they needed to recognise Hinton’s contribution in some way. Others like Gary Marcus or Jürgen Schmidhuber are much more critical.

Either way, this is also a moment of the zeitgeist, perhaps mirroring our excitement with electricity at the end of the 19th century. (Of course, polite society was head over heels about radium then, too. Perhaps something to think about?)

Congratulations to all recipients!

Here’s why I am stoked about the recognition of AI in chemistry…

🤔 Why humanity needs AI

Originally published on 7 September

Humanity’s fundamental characteristic is its ability to create knowledge. This ability sets us apart from other species: our ability to create knowledge, compound it, develop tools and systems that apply it and foster more of it.

I like David Deustch’s definition: Knowledge says something true and useful about the world. Knowledge is information with causal powers. It allows things to control other things. It is fallible and can be improved through a process of correction and criticism. And we can see how human-created knowledge does all that and is quite distinct from the instinctual knowledge or problem-solving of other animals, or the process by which selection creates biological knowledge.

Many of the problems we face today are problems of insufficient knowledge. Smallpox is the only infectious disease we have known to have been eradicated. Growing up in Zambia, I received a smallpox vaccine. I remember the grotesque needle and, even worse, bulbous pustule that grew on my arm in the days after. Two years later, the World Health Organisation announced smallpox had been eradicated. That was a triumph of knowledge! The immunological knowledge that led to the development of several vaccines, the epidemiological knowledge to put an eradication campaign together and the logistical know-how to execute it.

Knowledge is, in some sense, a solution.

Over the millennia, we’ve created a lot of useful knowledge: the importance of potable water, our understanding of the periodic table to make sense of the material world, how relativistic effects can be harnessed to provide precise locations on the planet, how to harness electricity to light the home, and much more besides…

Our ability to create knowledge is a function of two things: (1) the number of people who can usefully contribute to its creation and (2) their productivity.

That productivity is a function of two other things: the tools they have to help them and the institutional culture that supports them. Tooling is obvious: microscopes, rules, telescopes, distillation flasks, Bunsen burners, computers and quadrants. They all help the process of science.

But culture’s impact can’t be understated. The cultural characteristics of the Enlightenment — secularism, reason, and a belief in progress, were an undeniable multiplier on our ability to create knowledge. Wealth, in turn, allows societies to push talented individuals into long-range projects like research rather than contributing to immediate subsistence.

Today’s knowledge recession

Yes, research productivity is declining, good ideas are harder to find and science is getting less bang for its buck. Matt Clancy makes a comprehensive argument that science is getting harder and provides an excellent assessment of these challenges. All the while, knowledge is more complex. There is more for scientists to absorb, funding-driven specialisation hurts, and technology can limit us, which are among the interrelated factors slowing down today’s scientific knowledge production.

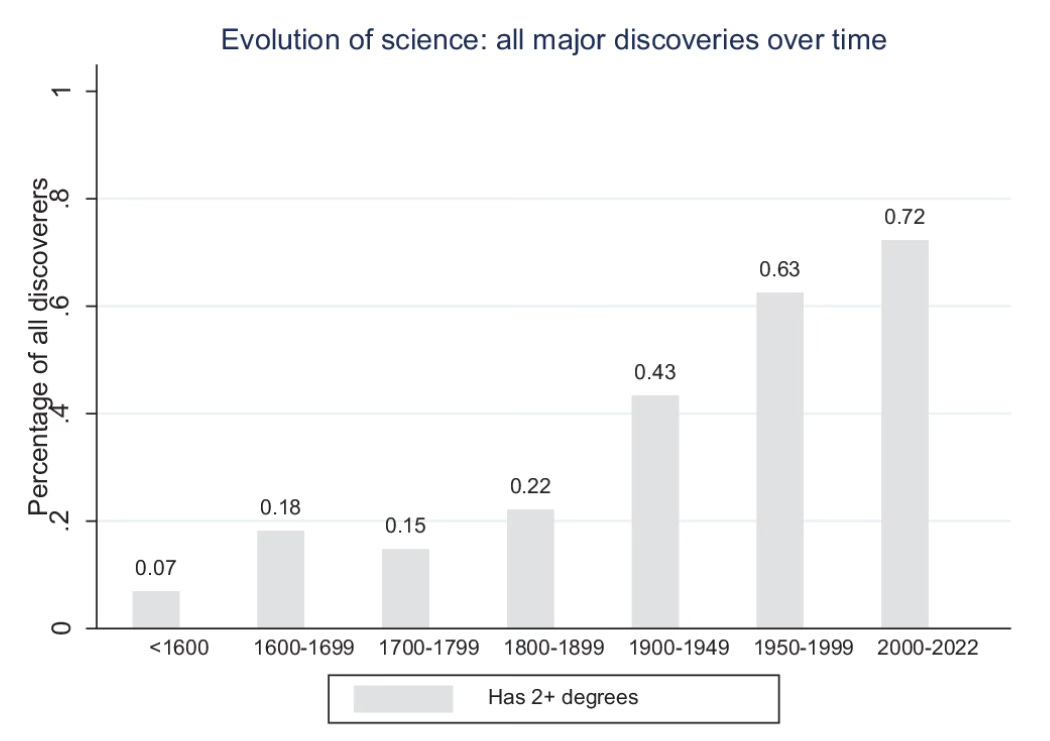

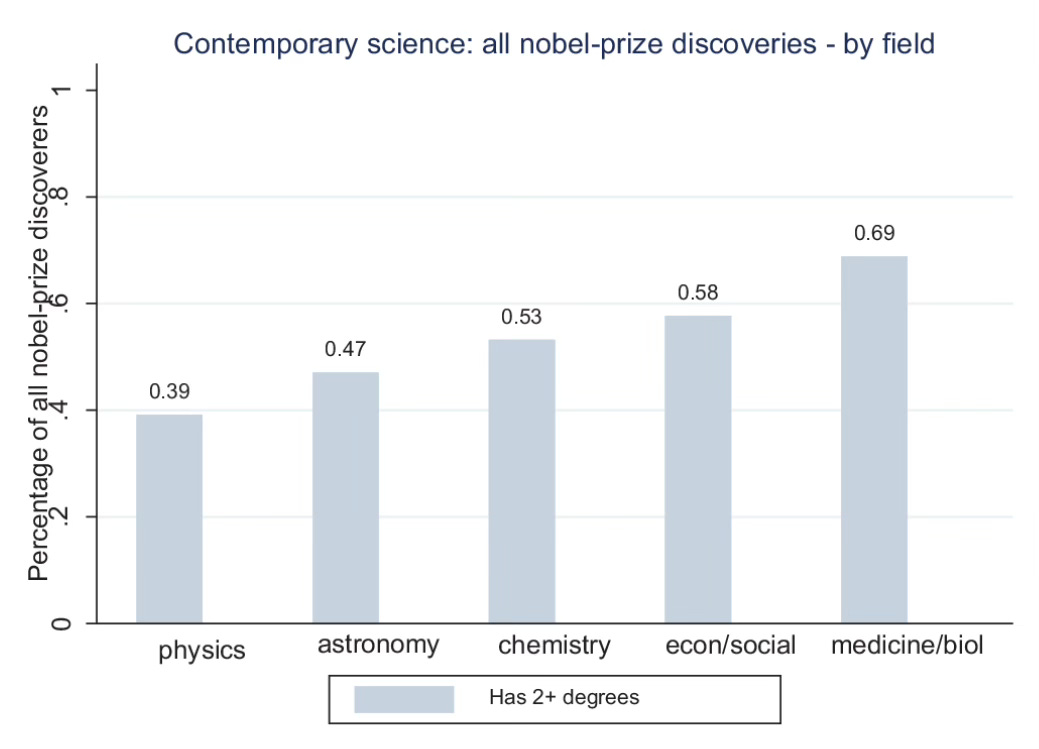

The most significant breakthroughs in science are disproportionately from the interdisciplinary scientists. Of science’s 750 greatest advances, more than half of Nobel-prize discoveries were made by scientists with two or more degrees in different academic fields. Yet the academy has for decades favoured increasing specialisation in favour of that much-needed grant.

Within a domain, scientific progress moves in fits and starts. A new technique provides low-hanging fruit and easy discoveries. As Samuel Arbesman points out, scientific discoveries follow an S-curve. We find lots at first, and then things slow down.

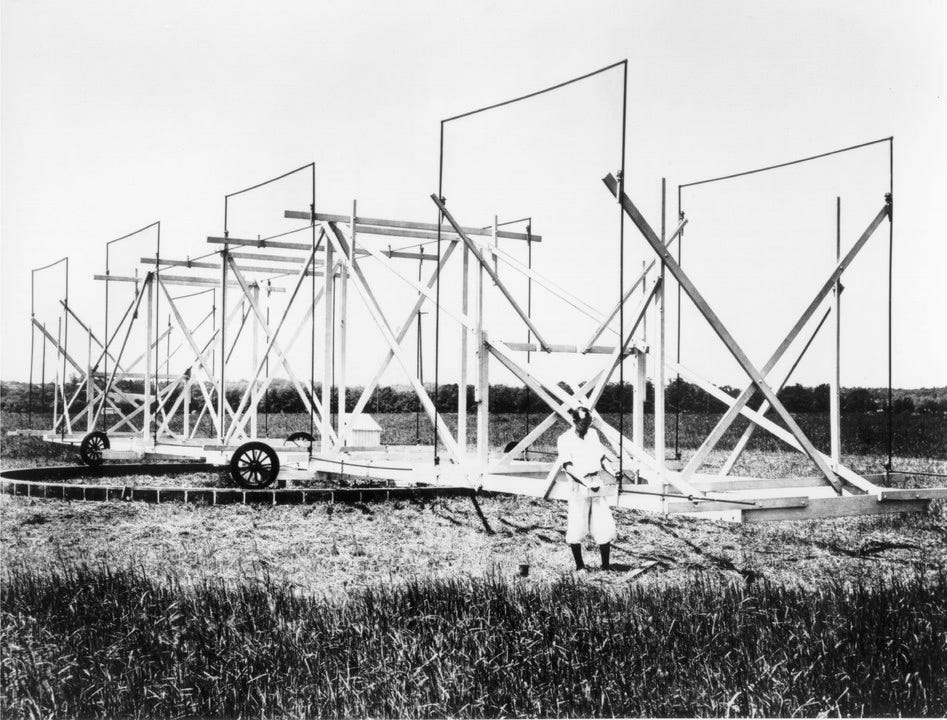

But a new technique will often emerge. There was a plateau in empirical astronomy at the turn of the 20th century. Optical telescopes help us understand the solar system, but at the turn of the 20th century as optical telescopes reached their limits, empirical astronomy plateaued. It took new tools to restart it, such as radioastronomy.

When we reached the limits, further breakthroughs continued with multispectral systems and telescopes in space. That compounding growth of knowledge moves in bursts as new methods become available.

I’m optimistic that new approaches to organising science will help unlock the productivity slump we’re living through. They may as well come from challenge labs, like DARPA and the UK’s Aria, or billionaire-funded “grand statement labs,” like Arc Institute. Another catalyst could be the geopolitical competition and flow of capital. Venture capital’s recent turn towards deeptech may increase the rate of technology transfer and the incentives for doing good science.

We’re approaching a turning point

I am not talking about the short-term question of why science seems to be getting harder. No. I’m thinking about a longer-term, more fundamental ceiling that two limits — less fungible — will proscribe.

The first is demographic. The human population has been rising for more than ten millennia, with one interruption—the Black Death—from which the population recovered within a century. In the coming century, things may change again.

We’re living longer and having fewer kids. Nearly every country will be below the replacement rate within a hundred years. Should those trends continue, the pool from which knowledge creation can be drawn will continually shrink. Even if we get richer and can afford more scientists, there will ultimately be a limit.

There is a second hard limit. We’re biological creatures.