🚀 Scaling climate technologies

Four blockers and how to remove them

I’m still puzzling over this question: how do we rapidly scale the climate tech we might need for the climate transition?

On the one hand, there are the dynamics of exponential technologies that are ultimately favourable. The exponential cost declines that we witnessed in solar photovoltaics, lithium-ion batteries and other technologies make these technologies affordable, often cheaper than fossil alternatives. Prices come down because of the interaction of learning-by-doing, modularity and productisation and large networks. These processes increase learning rates and market size, resulting in further learning and economies of scale. It also creates new markets — and the incentive for firms to invest in them. Such markets foster innovations in complementary industries (both upstream, amongst suppliers) and downstream (amongst service providers and operators) as a new industrial ecosystem takes hold.

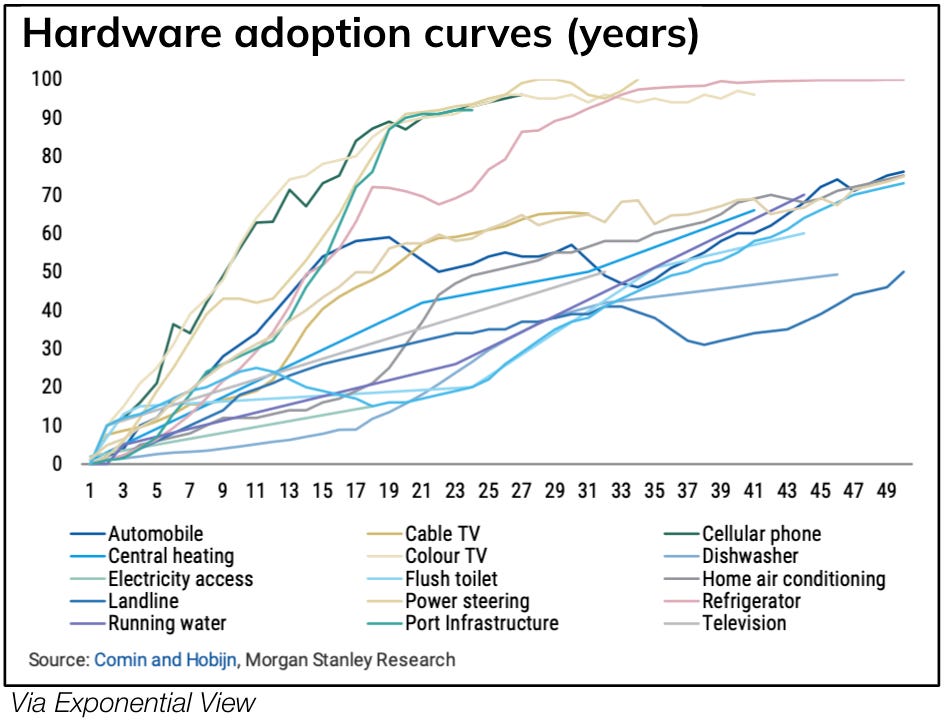

This process isn’t magic. And it can happen very quickly. Many technology transitions (consider that being from 10% market penetration to, say, 70%) take place in 12 to 15 years, even when these transitions involve hard physical stuff, like factories. The UK’s shift from ICE cars to electric ones looks like it might take around six years.

However, technology transitions require capital. This means firms or financial investors must be clear about the return they will get on that capital. If they aren’t clear, because it isn’t obvious when a market will form, they will dither.

Four things get in the way…

One is the speed with which material resources (mostly lithium being the one to worry about) can be accessed. I wrote about this here.

The second is permitting, policy and regulation. In many cases, it may take decades to get approvals to build new mines (which may be essential for lithium and other critical minerals), often due to the ancient legislation that governs such projects. But regulation, for example within the electricity industry, may favour old-school players and their one-way power grids, rather than a world of spiky renewables, operating at many different scales in a digitised two-way grid. Take the US, where plans on updating the power grid are proceeding snail-like: “The politics is a freakin’ nightmare.” Bad laws or unclear regulations make it less appealing for investors to invest. Part of the appeal of a climate tech accelerator like Elemental is its track record in working through these types of issues.

The third is a poor understanding of the science. Consider physics and the hydrogen boondoggle. The physics of the gas, as Michael Liebreich explains here, does not favour many of the mooted uses of clean hydrogen. That is not to say that there will not be a meaningful hydrogen industry, just not doing many of the things people think it will be doing. (Certainly not road transportation for one.)