How “95%” escaped into the world – and why so many believed it

Challenging sloppy thinking

Hi all, today’s post is open to all in the service of public discourse and anti‑slop thinking.

One number still keeps turning up in speeches, board meetings, my conversations and inbox:

“95 percent”

Do I need to say more than that? OK, here’s another clue: this number traveled on borrowed authority in 2025, rarely with a footnote and it started to shape decisions.

The claim is this: “95 percent” of organizations see no measurable profit-and-loss impact from generative AI. Of course, you know what I’m talking about. It has ricocheted through Fortune, the FT, The Economist, amongst others.

Often presented as “MIT / MIT Media Lab research,” the “95 percent” is treated as a settled measurement of the AI economy. It’s invading my conversations and moving the world. I’ve heard it cited by executives as they decide how to approach AI deployments and investors who use it to calibrate risk.

This number basks in the glow of MIT, the world’s best technology university. And I started to wonder if this evidence had truly earned that halo. Turns out, I’m not the only one – Toby Stuart at the Haas School of Business wrote about it as an example of how prestige and authority can turn a weak claim into an accepted truth.

Late last year, I tried to trace the claim back to its foundations. Who studied whom, when and what counted as “impact”? What makes the “95 percent” a number you can rely on, rather than a sop for clickbait? I also reached out to the authors and MIT for comment. I’ll share today what I found.

The paper trail

The original report was produced in collaboration with the MIT NANDA Project. The NANDA project was, at the time the report was published, connected to the Camera Culture research group of the MIT Media Lab. MIT’s logo is the only logo that appears in the document. The phrase “MIT Media Lab” doesn’t appear in the document.

The paper’s two academic authors, Associate Professor Ramesh Raskar and Postdoctoral Associate Pradyumna Chari, both affiliated with the same Camera Culture research group at MIT Media Lab. There were two other authors, Chris Pease, an entrepreneur, and tech exec Aditya Challapally.

The first sentence of the Executive Summary is the one that set the newswires crackling:

Despite $30-40 billion in enterprise investment into GenAI, this report uncovers a surprising result in that 95% of organizations are getting zero return.

It suggests that they sampled a certain number of organizations. And this is where my issues with this paper start.

Issue one: No confidence intervals

To demonstrate the arithmetic, let’s use the sample size of 52. This was the number of interviews in the research. If 95% said they got no return, then the math is simple.

Obviously, you can’t have 49.4 organisations reply “we had failure”, it’s either 49 or 50.

This in itself is problematic. If it were 50, the real success rate is 3.8%. If 49, it is 5.8%.

But even this is naive on two further counts: it’s a sample and it might not be representative. The sample size in question here is possibly as low as 52 (the number of interviews conducted), although it might potentially be higher (see issue two below). The universe of organizations is much larger.

Ergo, we have a sample of the whole universe. Academic convention is to provide confidence intervals when you have a sample, not a census. For a sample of 52-ish from an unspecified large-ish population, the confidence intervals are roughly +/- 6%; it would drop towards +/- 3% as the sample size rises to the low hundreds.1 The paper provided no confidence intervals around the 95% number, breaching academic convention.

The paper’s research appendix says that confidence intervals were calculated using “bootstrap resampling methods where applicable.” The bootstrap method is valuable in that it doesn’t make prior assumptions on the data distribution; however, small samples produce wider intervals, reflecting greater uncertainty. If you ran a bootstrap calculation on a sample size of 52 which had 49 or 50 failures, your confidence interval is between 100% failures and 86.5% failures (using the 49/52 figure. The value for 50/52 failures sits at 90.4% to 100%). This interval means the true value is probably somewhere within a margin covering 13.5 percentage points. Reporting this figure as a single 95% value completely hides the underlying uncertainty – that failure rates in their sample are likely between the high-80s and 100%. That is a highly volatile range which shakes my confidence despite the methodological signalling.

Issue two: The sample is not representative

But given this is clearly a sample, is the sample representative? A number that blends interviews, conference responses, and public case studies, as the MIT NANDA study did, can be useful as a temperature check. But it is not, on its own, a reliable portrait of “organizations” in general. The researchers mixed 52 structured interviews, analysis of 300 public AI initiatives (out of how many? which 300 were chosen?) and 153 surveys of non-specified “senior leaders.”

Page 24 of the report, section 8.2, does in fact acknowledge the limitations of the sampling technique: “Our sample may not fully represent all enterprise segments or geographic regions” and “Organizations willing to discuss AI implementation challenges may systematically differ from those declining participation, potentially creating bias toward either more experimental or more cautious adopters.”

The sample period itself is fundamentally flawed. It spans January to June 2025, a full six months. Consider this timeline. If the earliest enterprise genAI projects launched in late 2023 or early 2024, respondents reported on efforts anywhere from twelve to eighteen months old. Yet a January 2025 interviewee might have started their project just three months prior, in late September or early October 2024. How can we meaningfully compare a three-month pilot to an eighteen-month rollout?

This survey window conflates projects at radically different stages of maturity and ambition, a serious methodological problem in any context, but especially damaging here. In 2024, enterprise AI spending grew by at least a factor of three (~10.6% compound monthly growth rate); in the first half of 2025, growth ran at 1.66x (equivalent to 2.75x annualized) according to our forecasts. Menlo Ventures estimates a 3.2x increase in enterprise AI spend in 2025. That pace of change, in usage patterns, in the composition of adopters, in the very definition of “enterprise AI,” renders a six-month survey window almost meaningless.

So, in fact, unless the researchers share their raw data, we have no idea whether the sample is full of early adopters, or early adopters with high expectations, or of people who consider themselves leaders but aren’t, or with people in fringe organizations that don’t represent the American firm. Nor do we have any sense whether people who answered “no” in January would have answered “yes” in June, had they been asked then.

Issue three: The changing denominator is bamboozling

The study mixes public data (which may or may not be representative) with two different types of interviews and surveys conducted over an extended period of time. It’s mush.

But then, let’s ask a question about what we are taking a proportion of. Imagine you have a high school year of 500: 250 boys and 250 girls. If you said 60% of boys and 70% of girls passed the math exam, it wouldn’t be reasonable to say 60% of students passed the math exam (you’ve ignored the girls). Nor would it be reasonable to say that 70% of the girls passed the physics exam (you only talked about having data for the math exam).

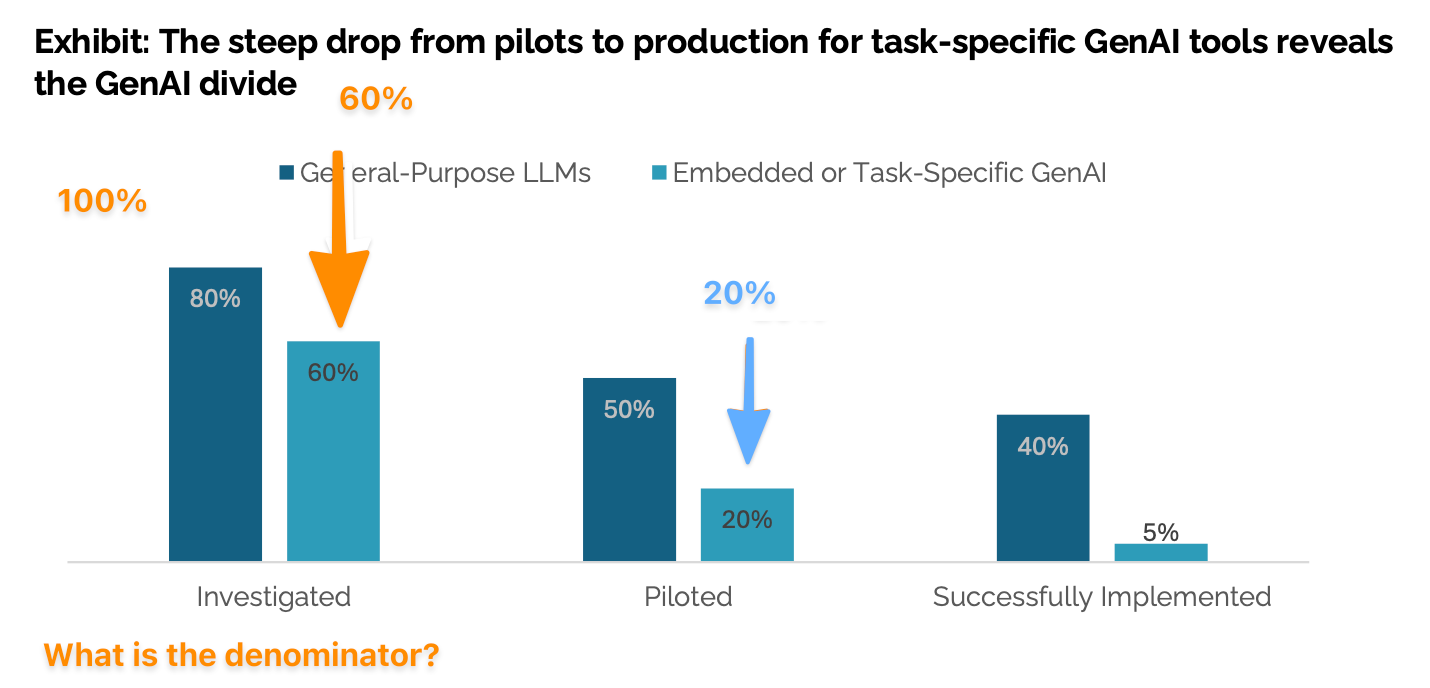

Yet this is roughly what the NANDA paper did. The denominator used is not consistently calculated. On page 6, a chart shows 5% of firms sampled successfully implemented an embedded or task-specific genAI tool. It also shows that 60% of firms investigated a task-specific tool.

The denominator in this case includes the 40% of firms that never even investigated the task-specific tool. If this were the case, if your firm never investigated using a task-specific AI tool, your non-investigation counts as a failure for these purposes.

The real maths – if these were consistent definitions and using “tools investigated” as the denominator – is:

The trouble is, the report contradicts itself. On page 3, the report states, “Just 5% of integrated AI pilots are extracting millions in value”. But this implies the denominator is pilots launched, the number marked by the blue arrow above. If that is the case, the real success rate is

A quarter is an incredibly high proportion – if true, we’d want to do more research to assuage our sceptical tingles.

But remember the introduction to the report. It states the “95% of organizations are getting zero return”, not organizations which ran AI pilots, but organizations, period.

Issue four: The method of defining “success” is not clear

What of the “measurable P&L impact”? Profit-and-loss isn’t like rainfall. Anyone who has run a business knows that. In large organizations, only a few people can ever really know, and it’s unclear how many of them would be the ones answering conference surveys or interviews. It’s also unclear that you could actually measure a P&L impact with good attribution in less than several months, even if there was such an impact.

The headline number smuggles in a claim about pace: “Top performers reported average timelines of 90 days from pilot to full implementation.” Does that mean to the P&L impact or to a technical roll-out? It is unclear.

Generative AI remains young as a corporate technology. The starting gun fired in late 2023. Enterprises typically need 18-24 months to move large-scale IT deployments from pilot to production – building systems, workflows, and governance along the way.

The report claims “only 5 percent” succeeded. But recall the fieldwork window: January to June 2025. This window means that some organisations might have even seen results during the fieldwork period if they were surveyed in January rather than June. The implication: an impossibly slow path from pilot to impact.

It seems like the study defines “success” so narrowly that “not yet” becomes “never.”

That is why the right way to treat “95 percent” is not as a fact. It is a crude signal being stochastically parroted in the peanut gallery.

What to make of these four glaring issues?

I wrote to the two MIT-affiliated academic authors, Prof. Ramesh Raskar and Dr Pradyumna Chari, to clarify.

I asked specific questions about the academic process. In summary:

Did the “95 percent” figure represent a statistical finding from the sample, or is it a rough directional estimate - and either way, what specific population of companies and projects does it describe?

What exactly counts as “measurable P&L impact” - how long after implementation did they measure it, how large does the impact need to be, and are they measuring individual projects or whole company performance?2

I did not receive a response to my enquiries.

So I had to escalate to MIT Media Lab’s leadership. Raskar and Chari are attached to The Media Lab, which operates as a research laboratory within MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning. The School of Architecture and Planning rolls up to the top level of the institute.

What MIT told me

Faculty Director of the MIT Media Lab, Tod Machover, did reply. MIT’s counsel, Jason Baletsa, was copied3.

In that correspondence, Professor Machover described the document as “a preliminary, non-peer-reviewed piece” created by individual researchers involved in Project NANDA. Machover told me that the NANDA research group now operates within an independent non-profit foundation. (Although the MIT Media Lab still maintains a NANDA research page.)

The report, I was told, was posted briefly to invite feedback. Indeed, it was posted on MIT’s website from 18 August to 16 September, according to the Internet Archive.

That framing – early, exploratory, posted for comment – is plausible. Academia must be allowed to think in public. Drafts and half-formed ideas are a reasonable part of the process of scholarship.

During the feedback period, one of the four authors of the report was quoted in the media. Much of the subsequent media coverage presented it as a finding, not as an early draft posted for comment.

But this is a problem, as much for MIT as it is for us. Treating casual, informal work as equivalent to scholarship doesn’t just mislead the market; it erodes the trust scaffolding that industry participants, investors, founders, and the public rely on to make decisions.

The report no longer appears on an MIT.edu domain. However, the PDF circulating online still carries MIT branding and is hosted on a third-party research aggregator. There is no canonical MIT-hosted version, no note explaining how it should be cited, and no institutional clarification that would stop the statistic from being treated as an MIT finding.

When I pushed further on the question of whether it is correct or incorrect to call this “a piece of research from MIT / MIT Media Lab” I didn’t initially get a clear answer.

Eventually, in an email dated 12 December 2025, Kimberly Allen, MIT’s Executive Director of Media Relations, wrote on behalf of the Provost and VP for Research4: “There were MIT investigators involved. It was unpublished, non-peer-reviewed work. It has not been submitted for peer review as far as we know.”

That’s somewhat helpful. The number had been acting as an institutional fact. “MIT says” has, with very good reason, a great deal of weight. The authors themselves say: “The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and reviewers and do not reflect the positions of any affiliated employers.”

But the paper still carries an MIT logo so people stumbling across it might read more into it than it may deserve. That brand continues to do the work for something that appears incomplete.

It is incredibly hard to get a role at a top university. “Insanely hard” is what one academic friend told me, precisely because the high standards of those organisations have produced a very costly external signal about quality.

Breaking the number

So what’s a more reliable reading? If you triangulate across what firms are actually reporting, and account for adoption lags and sampling bias, can we narrow the plausible space for ‘no enterprise-level, clearly measurable P&L impact yet’?

The strongest part of the rewrite lives with the denominator. The 5% number emerges, with huge confidence intervals, from the research if the denominator includes every organization that didn’t even try to implement a task-specific AI. This is like stating that I failed to board the American Airlines flight from JFK to Heathrow last Thursday. True, but I wasn’t booked on the flight. I wasn’t even in New York that day.

And if you consider a more reasonable denominator: those who tried to implement such an AI through a pilot, you end up with a success rate of 5 out of 20, or 25%. The error margins? Possibly in the range of +/- 15%; so a 10 to 40% success rate based on running this through a handful of reasoning LLMs at the highest thinking mode. If you make more aggressive assumptions about sampling flaws and shaky definitions, the dispersion widens further.

If the underlying data was shared by the researchers, we could do a much better job of this. But it isn’t clear why anyone should make any type of decision based on this.

A defensible inference band sits in the low-80s, not the mid-90s of organizations that started pilots on task-specific AI, not seeing results at some point between January and June 2025. But it is plausible that number could be much lower.

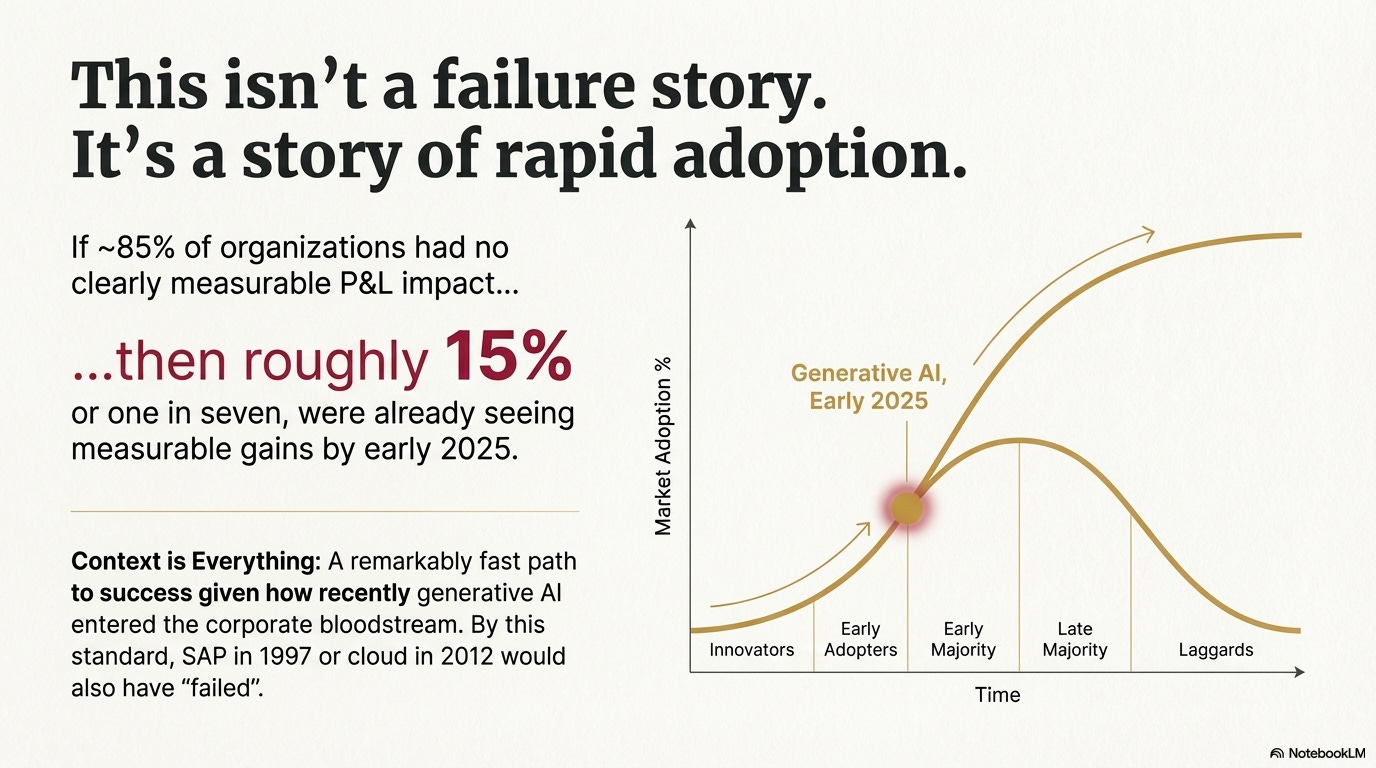

It certainly isn’t the nihilistic “95 percent” that markets have begun to quote as if it were an MIT-certified measurement. By this standard, SAP in 1997 or cloud in 2012 would also have failed.

Put plainly, if around 85% of organizations had no clearly measurable P&L impact, then roughly one in seven were already seeing measurable gains by early 2025. A remarkably fast path to success given how recently generative AI entered the corporate bloodstream. And I’m being conservative, it could easily have been much higher, one in five or more.5

This is a far more nuanced picture than “95 percent failure” – a headline that invites either complacency (“AI is hype”) or fatalism (“it’s impossible”).

Orphaned stats, and the fix

Go one level deeper, and the real issue isn’t whether the number is 95, 86, 51, or 27 – it’s that the “95 percent” has become an orphaned statistic. We’re familiar with orphaned numbers. Like we only use 10% of our brains. That it takes seven years to digest swallowed gum. That Napoleon was short. The goldfish has a 3-second memory. That there are three states of matter. It’ll be cited… just because.

But, unlike the goldfish that forgot Napoleon was average for his time, this statistic has a halo. And this number has moved capital. It has travelled faster than its caveats. It will end up embedded in investment memos long after anyone remembers to ask what they actually measured. Worst of all, it forces the reader to do basic provenance work that much of the commentary ecosystem waved through.

So here is the standard that should apply. If a statistic is going to be cited as “MIT research,” it deserves, at minimum, a stable home and enough transparency that a sceptic can try to break it. And if it shouldn’t be cited as such, its providence should be clearly explained by the institution and by its authors.

Until that happens, the “95 percent” figure should be treated for what it is: not reliable. It is viral, vibey, methodologically weak and it buries its caveats. The report served some purpose, but what that purpose is, I’m not clear.

If – big if – 15-20% of large organisations were already translating generative AI into measurable gains at the start of last year, that is not a failure story. It is the rapid climb up the right tail of a diffusion curve. So rapid in fact that we’d want to sceptically unpick any data that suggested that.

So how certain am I that this 95% statistic, so beloved by journalists and those in a hurry, is unreliable?

One hundred percent.6

Using the rule of thumb that for a binomial proportion, an approximate two-sided 95% margin of error is

where p is the proportion observed in the sample, and n is the sample size.

These are condensed versions of longer questions I asked.

Baletsa is a counsel of MIT as a whole.

To help understand the structure here: The Provost is effectively the Chief Academic Officer. The VP of Research is responsible for academic quality. The Deans of a School (such as the School of Architecture and Planning) would report to the Provost. Faculty Directors (of particular labs within a School) would usually report into a Dean of a School.

But we can’t know, given all the shortcomings in the data as released.

I’m 95% sure that I’m 100% sure.

Thank you for checking this stat. It has been on my list to do as I was super skeptical when I saw it everywhere.

"60% of the time, it works every time"