Hi, it’s Azeem.

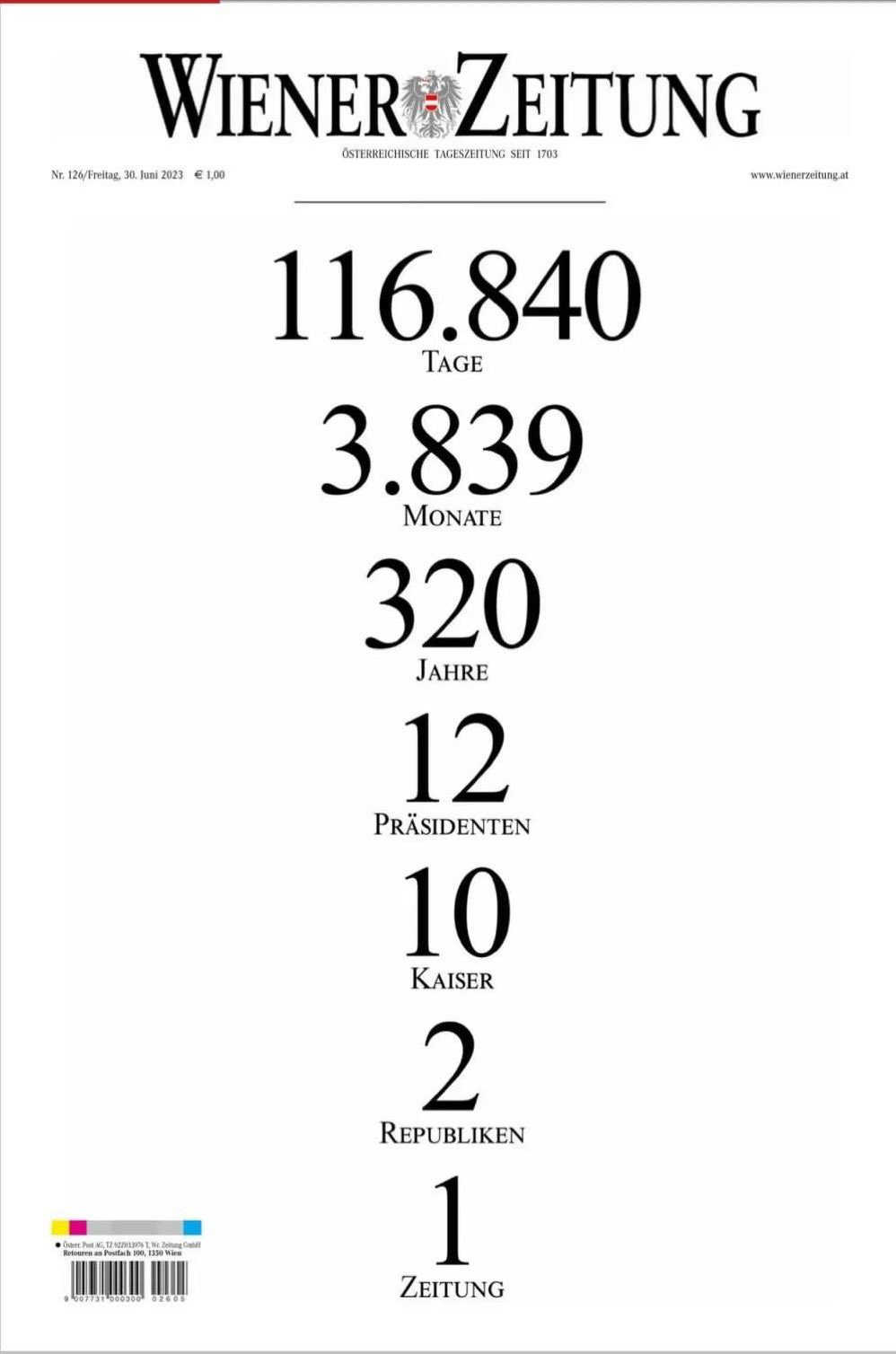

Today, Wiener Zeitung, the oldest continuously published newspaper in the world, was printed for the last time. It signed off the Gutenberg era with this epic front page.

The Gutenberg press was a disruptive technology that expanded the creation and application of information in human society. The world of information in which we now live, and the laws that govern it, was built on the foundations of the printing press—and three hundred years of commercial, social and economic power politics.

One such institution that takes a starring role in arguments of the economics of creativity is copyright: a set of rules created to enrich not authors but the emerging publishing industry.

To understand how we could think about copyright in the age of AI and ChatGPT, I’ve asked Jeff Jarvis, the Leonard Tow Professor of Journalism Innovation at the Craig Newmark Graduate School, whom I have known for more than 20 years, to share his thoughts on the topic. I love his proposal and believe it is something from which we can build.

Amongst many accolades, Jeff is one of the leading practitioners and thinkers in the field of journalism and digital media. Deeply thoughtful, he is the author of several bestsellers.

This essay is based on the work of his new book, The Gutenberg Parenthesis. I’ve been lucky to read it — and I do recommend you order it today.

Please take a moment to thank Jeff for taking the time to lay out his argument by sharing this guest edition with your network or dropping a comment below.

Cheers,

Azeem

The Gutenberg Parenthesis—the theory that inspired my book of the same name—holds that the era of print was a grand exception in the course of history. I ask what lessons we may learn from society’s development of print culture as we leave it for what follows the connected age of networks, data, and intelligent machines—and as we negotiate the fate of such institutions as copyright, the author, and mass media as they are challenged by developments such as generative AI.

Let’s start from the beginning…

In examining the half-millennium of print’s history, three moments in time struck me:

After Johannes Gutenberg’s development of movable type in the 1450s in Europe (separate from its prior invention in China and Korea), it took a half-century for the book as we now know it to evolve out of its scribal roots—with titles, title pages, and page numbers. It took another century, until this side and that of 1600, before there arose tremendous innovation with print: the invention of the modern novel with Cervantes, the essay with Montaigne, a market for printed plays with Shakespeare, and the newspaper.

It took another century before a business model for print at last emerged with copyright, which was enacted in Britain in 1710, not to protect authors but instead to transform literary works into tradable assets, primarily for the benefit of the still-developing industry of publishing.

And it was one more century—after 1800—before major changes came to the technology of print: the steel press, stereotyping (to mold complete pages rather than resetting type with every edition), steam-powered presses, paper made from abundant wood pulp instead of scarce rags, and eventually the marvelous Linotype, eliminating the job of the typesetter. Before the mechanization and industrialization of print, the average circulation of a daily newspaper in America was 4,000 (the size of a healthy Substack newsletter these days). Afterwards, mass media, the mass market, and the idea of the mass were born alongside the advertising to support them.

One lesson in this timeline is that the change we experience today, which we think is moving fast, is likely only the beginning. We are only a quarter century past the introduction of the commercial web browser, which puts us at about 1480 in Gutenberg years. There could be much disruption and invention still ahead. Another lesson is that many of the institutions we assume are immutable—copyright, the concept of creativity as property, mass media and its scale, advertising and the attention economy—are not forever. That is to say that we can reconsider, reinvent, reject, or replace them as need and opportunity present.

From copyright to creditright

Take copyright. As a doctrine and a business model, if not a law, it has been doomed since the day the first cheap and easy digital copy of media was made. I am old enough to remember when copyright was going to stop the VCR (hell, I’m old enough to remember the VCR) and then the DVR. But consumer demand was just too great; copyright lost.

The copyright legislation SOPA-PIPA (Stop Online Piracy Act and Protect IP Act) went down in flames in 2012 when Silicon Valley stood up against Hollywood. But that same year, news publishers in Germany cashed in their political capital to buy votes for protectionist legislation aimed at forcing platforms to pay them for the privilege of linking to their content. Such lobbying next spread to Spain, the rest of Europe, and Australia, and today, the US, Canada, and California are working on their versions of the legislation.

Copyright is outmoded. A few years ago, I moderated a series of discussions for the World Economic Forum on copyright and supporting creativity. In the safe environs up the Magic Mountain in Davos, media executives would confess that copyright is no longer fit for purpose—though they will fight to retain its protections until their last breaths. Through these discussions with creators, media executives, and policymakers, I concocted a different concept I call creditright.

If we acknowledge that art is an act more than an artifact and that many parties can collaborate in creation, then we need means to record, recognize, and reward those contributions.

Imagine, for example, if someone tells a story, which inspires a poem, which becomes the basis of song lyrics, to which someone adds a tune, and someone else performs it, while others produce and record the song, while fans share and promote and reuse it. It would be useful to have a way to give credit to everyone who contributes to that chain of creativity so they might be rewarded—whether with remuneration or merely acknowledgment—and to encourage such behavior in the service of art. I won’t argue that my concept of creditright is necessarily feasible—or certainly that anything like it could quickly displace the institution of copyright—but we do need to consider such new perspectives, new models, and new institutions.

And all these were critical concerns before large language models charged through the china shop of data media models, antiquated copyright law and the very value of content. How should we make sense of the impact of ChatGPT and its cousins?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Exponential View to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.