🔮 Sunday edition #534: Superintelligence; runaway climate; brittle agents; fusion gold++

An insider’s guide to AI and exponential technologies

Hi all,

Welcome to our Sunday edition, when we take the time to go over the latest developments, thinking and key questions shaping the exponential economy.

Thanks for reading!

Azeem

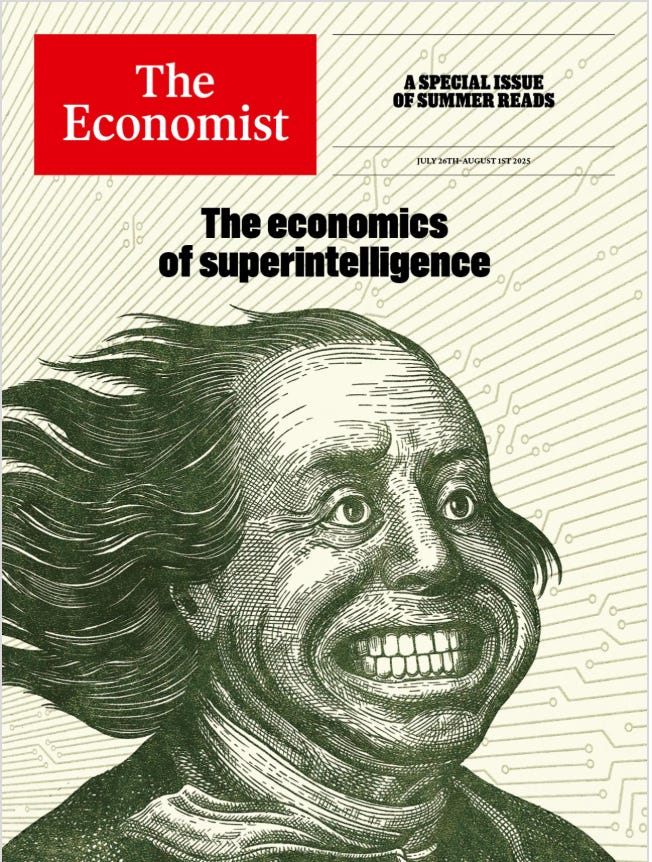

The economics of superintelligence

The idea of an AI-transformed economy has escaped the margins of niche blogs and podcasts. This week, The Economist made it its cover story: humanity’s next step could be machines that automate the generation of ideas. Not just labour, but thought. If that happens, growth could explode.

But their more immediate concern is the fallout between the haves (the owners of AI capital) and the have-nots (everyone else). The pressure to redistribute, regulate or surveil is set to overwhelm existing institutions.

One such institution is the job. As investor Lawrence Lundy-Bryan puts it, the job – once a vessel for income, identity, and social legibility – is fracturing. AI is eroding the scaffolding that made careers coherent. Early-employee ladders splinter as firms think through automation.

And those decisions matter. As I wrote just recently, when firms automate high-expertise tasks, wages fall but employment rises. When they automate routine tasks, employment shrinks but pay rises. Either way, the wage ladder bends. The job’s structural role in society weakens.

This will likely have tangible effects before any long-horizon superintelligence arrives. Political commentator Robert Shrimsley warns that the last wave of disruption hit blue-collar workers. This one targets the professional middle class, whose secure jobs underwrite political moderation. If this security disappears, the legitimacy of the system itself starts to crack.

There’s no doubt that superintelligence can provide incredible benefits. But before we can talk seriously about a superintelligent economy, we may need to confront an immediate, unstable one.

See also: Mark Zuckerberg says that Meta is seeing early signs of self-improvement in its AI models.

When rare becomes predictable

Antarctic sea-ice has collapsed to levels four standard deviations below the 1991–2020 average. Statistically, that should happen once every 31,600 years. And yet, it’s happened three times in the past 24 months.

Its ripple effects on ocean currents, weather systems, and ice-sheet stability will be enormous. Physics doesn’t negotiate. Nor does biology.