🔮 The Sunday edition #501: The new Manhattan Project; AI nanobodies; nitrogen from nothing, octopus overlords & MP3 ghosts++

An insider's guide to AI and exponential technologies

Hi, it’s Azeem. Welcome to the Sunday edition of Exponential View no. 501. Nvidia’s latest numbers are impressive and I’ll contextualise the performance for members on Monday. In the meantime, I’ll draw our attention today to a more fundamental challenge brewing beneath the surface: the race for raw computing power. China is quietly winning where it matters most - energy infrastructure. Lots to cover in today’s edition — enjoy!

Ideas of the week

Are we facing an AI-powered wage collapse?

Continuing improvements in AI could trigger a collapse in wages across broad segments of the workforce, University of Virginia professor Anton Korinek suggested in an essay for the IMF last year. The good news: AI should be very good for growth. The better news: wages will rise. The unsettling news: those wage curves are inverted parabola. Wages plummet toward zero as AI systems become increasingly capable. Here is the adaptation story we’re missing.

The new Manhattan Project

America wants its own Manhattan Project for “AGI”. The bipartisan US-China Economic and Security Review Commission has proposed an ambitious programme to Congress to prevent China from overtaking America’s lead in AI. The original Manhattan Project only cost about $30 billion in today’s terms, equivalent to the amount VCs invested in generative AI in 2023 alone.

However the critical challenge isn’t financial, it’s infrastructural. And this is where the government can significantly help. The United States has a head start in the industry and the finances, but it lacks access to energy – potentially diminishing the nation’s current advantage. Over the past decade, China has added 37 nuclear reactors to its grid. The US? Just two. AGI is likely to require a lot of energy to build and to run in the coming years. If the US can’t cut through regulations and mobilise resources to invigorate its energy infrastructure buildout, China could have the momentum to overtake.

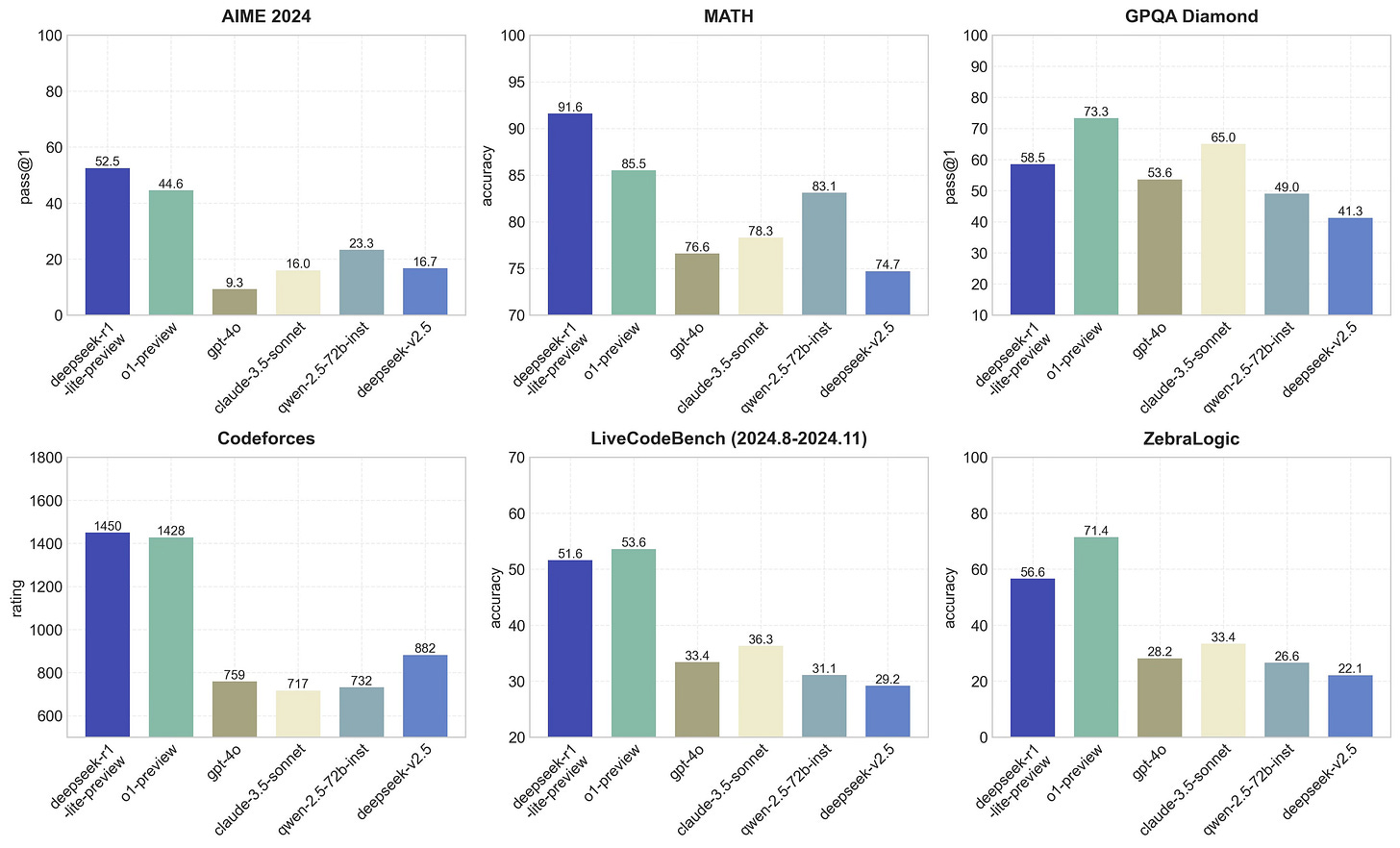

China has already turned adversity into advantage. In a dialectical irony that would make Marx proud, the very constraints of chip sanctions have pushed it to develop remarkably efficient models, such as DeepSeek, rivalling OpenAI’s o1 on benchmarks.

See also:

While most countries can’t compete with the US and China in frontier AI development, they can still find strategic niches to thrive in the AI revolution. Eric Schmidt’s column in The Economist is worth a read.

Leading by example

For the first time, the UK and US AI Safety Institutes conducted a joint pre-deployment evaluation of a new model, Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet. The findings revealed that “jailbreaks” could circumvent the model’s safeguards, a vulnerability shared with other AI systems. This kind of transparent disclosure of potential weaknesses, rather than obscuring them, is a positive development. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, whom I spoke with about the company’s approach to AI development a year ago, was on the Lex Fridman podcast recently. He shared the theory of change driving the internal work:

Anthropic’s mission is to try to make this all go well. And, we have a theory of change called race to the top. Race to the top is about trying to push the other players to do the right thing by setting an example. It’s not about being the good guy – it’s about setting things up so that all of us can be the good guy.

The best kind of AI

Every week, there’s new evidence of AI as an accelerant in scientific research. Here’s the latest…

Stanford University researchers set up a virtual AI lab that created 92 new nanobody designs, including multiple nanobodies with successful binding activity against the virus that causes Covid-19 and nanobodies that are active against recent variants. AI chipmaker Nvidia launched a new microservice using AI simulation that can test 16 million chemical combinations in hours instead of months.

Particularly interesting for social research: a team at Stanford “cloned” human personalities and integrated them into AI agents in a simulated town. The agents performed with 85% accuracy on the General Social Survey compared to humans replicating their own answers two weeks later. This type of work could be applied in social sciences research to improve precision, or used to test policy decisions for unanticipated second- or third-order effects before real-world implementation.